An earlier post of mine, on ‘what counts as evidence’, generated a healthy debate, and I thought I could leave the thorny problem of ‘what works’ in education for a while. Maybe lighten the mood with a blog about the all-out assault on the judiciary in post-Brexit Britain, or what’s an appropriate response to a Donald Trump presidency, something like that.

But the ‘evidence’ issue reared its contentious head again yesterday, November 4th, so The Donald might have to wait.

The flashpoint was the publishing of a report by the Educational Endowment Foundation (the UK equivalent of America’s What Works Clearinghouse) on the impact of Project-Based Learning on literacy and engagement.

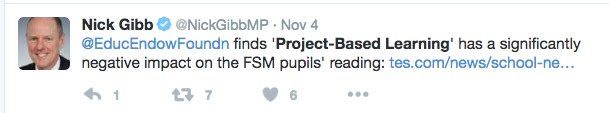

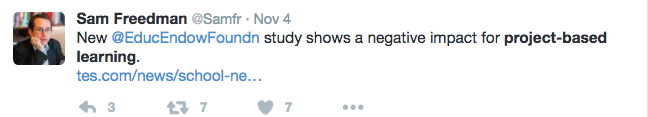

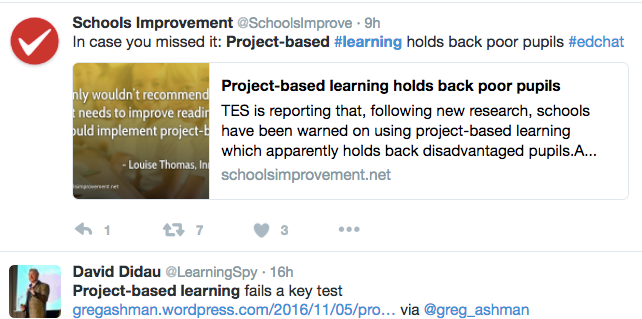

The Times Educational Supplement was the first to claim “Exclusive: Project-based learning holds back poor pupils”. And the predictable social media onslaught ensued:

It soon became abundantly clear that hardly any of the Tweeters had bothered to read the actual report. In fact, I doubt very much that many of them had even gone beyond the abbreviated version of the TES article, the fuller version of which is only available on subscription So, before we go any further, please spend 5 minutes reading the EEF summary here. Better yet, read the full report.

The summary doesn’t get off to a great start with an bizarrely restrictive definition of PBL:

“Project Based Learning (PBL) is a pedagogical approach that seeks to provide Year 7 pupils with independent and group learning skills to meet both the needs of the Year 7 curriculum as well as support their learning in future stages of their education.”

But let’s move on to the gist of the conclusions:

“Adopting PBL had no clear impact on either literacy (as measured by the Progress in English assessment) or student engagement with school and learning.” Perhaps mildly surprising as PBL is often touted – by people like me – to enhance student engagement. Otherwise, nothing to see here.

“The impact evaluation indicated that PBL may have had a negative impact on the literacy attainment of pupils entitled to free school meals. However, as no negative impact was found for low-attaining pupils, considerable caution should be applied to this finding.”

I confess I’ve read this statement repeatedly, and I’m still none the wiser. Are free school meals students therefore not ‘low-attaining’? If considerable caution should be applied, why draw the conclusion in the first place?

This was the focus of the TES headline. Their journalist clearly read the full EEF report, but didn’t think it their responsibility to draw attention to the caveat ‘overall, the findings have low security…47% of the pupils in the intervention and 16% in the control group were not included in the final analysis. Therefore there were some potentially important differences in characteristics between the intervention and control groups. This undermines the security of the result. The reason that so many pupils from schools implementing PBL are missing from the analysis is largely due to five of these schools leaving the trial before it finished. The amount of data lost from the project (schools dropping out and lost to follow-up) particularly from the intervention schools, as well as the adoption of PBL or similar approaches by a number of control group schools, further limits the strength of any impact finding.”

So, almost half of the schools had to drop out (for reasons which we’ll come to in a moment). Furthermore, the intervention period was meant to be two years but, due to funding constraints, this was halved. This is significant because most PBL experts agree that it takes 3-5 years before teachers really feel confident delivering a different pedagogical approach, and can therefore expect high quality student outcomes, whereas one can assume that the control group of schools have been working in their ways for some considerable time.

And if that’s not enough to cause doubt, consider this from the report:

“ for some that did not get allocated to the intervention group, faithfully adopting the control condition was seen as being detrimental to their pupils’ learning and therefore some of these schools chose to implement a version of PBL anyway.”

(Full disclosure: I can confirm this took place. Although I’m a Senior Associate at the Innovation Unit, who managed the trial, I was not part of the team. I do, however train schools in the use of Project-Based Learning. I discovered at the end of a training event that the school I’d been training were part of the control group and were intending to introduce PBL to their students. Contamination of evidence is anathema to educational researchers and further undermines the usefulness of the conclusions.)

Another central tenet of randomised control trials is that like is compared with like: if you want to know whether an intervention will improve literacy scores, you should have schools that were comparable before the intervention began. According to the Innovation Unit blog post in response to the report: “8 of 11 schools in the study were ‘Requires Improvement’ (an OFSTED categorisation indicating cause for concern) or worse (national average is 1 in 5)…The control group were stable in comparison, with 8 of 12 schools Good or Outstanding” .

So, here’s the nub of it: the newspaper article claimed that the report demonstrated that “FSM pupils in project-based classes made three months’ less progress in literacy than their counterparts in traditional, subject-based lessons.”

But this was based upon literacy data from schools – 80% of which would have already had poorer test scores than most of the control group schools. Is it possible, therefore, that the kids tested might have actually been further than 3 months behind their control group counterparts, without the PBL intervention?

Let’s use a simpler analogy in order to highlight this flaw: If you feed me anabolic steroids for a year, I’ll still come in a long way behind Usain Bolt in a 100m race. Surely a more sensible test would have been to see if my own personal times improved after the ingestion of drugs, not whether I was able to beat someone already faster than me?

Some on Twitter justifiably asked why was almost half of the data missing from the intervention schools, but not the control group? It turns out there were a variety of reasons, most of which point to the difficulty of carrying out trials in the fear-driven English schools system. 5 of the 12 intervention schools withdrew during the trial. 3 had a change of headteacher (presumably in response to OFSTED judgements), 2 were taken over by academies. 1 withdrew after the trial was cut from 2 years to 12 months. One school refused to submit its students to the test, arguing (with some justification) that you can’t hope to see improvements in literacy scores 12 months after introducing PBL.. If you, as a leader, were facing future closure if results didn’t improve, would you introduce a significant change like project-based learning, or knuckle down, and overdose on test-prep? Yep, me too. So, does it make sense to study the impact on such schools?

Before I get on to the two ‘J’Accuse’ parts of this post, allow me to share a few quotes from the evaluators report:

“ it is not possible to conclude with any confidence that PBL had a positive or negative impact on literacy outcomes”

“ schools reported finding positive benefits from the programme in terms of attainment, confidence, learning skills, and engagement in class”

“ the Innovation Unit’s Learning through REAL Projects implementation processes were particularly effective for the target (that is, willing and with the capacity) schools, and the feedback from those schools was almost entirely positive.“

“The need for improving skills appropriate for further study and those valued by employers in the modern workplace (a central aim of PBL) has not diminished, but probably increased. This study picked up the value of these skills to pupils’ learning and future potential through the process evaluation, but was not able to measure these skills as an outcome.”

Were any of these quoted by the TES? Of course not. I realise that “Study Doesn’t Prove Much Of Anything” is a kind of headline more suited to The Onion than the TES, but journalists have a responsibility to provide balance, especially in the education press, as we’re living in an evidence-based era. If they don’t provide that balance, we may as well just forget about truth and see who can shout the biggest lie. The evaluators, it seems to me, did a good job in presenting a fair and balanced assessment, working within the constraints of a difficult set of circumstances, on a project that probably should have been curtailed when so many schools dropped out.

It’s just a pity that the ideological bias of our media sought to significantly misinterpret it.

Which brings me to my second accusation. I don’t think I’m being unfair when I say that, in the increasingly fractious educational debate between ‘traditionalists’ and ‘progressives’, there are a greater proportion of traditionalists who say that we should objectively look at the evidence, and make informed policy and practice decisions, on the facts, not misinterpretations.

So, it was particularly disappointing to see some of those same people jump on the TES headline, rather than reading the evaluators report. Sadly, this includes Nick Gibb, Minister of State for School Standards:

and Sam Freedman, Director of Teach First:

and SchoolsImprovementNet:

And a host of others on Twitter.

Rachel Wolf, of Parents and Teachers for Excellence, was quoted in the TES article (because I’m sure she’d read the full report), citing students doing a project on slavery, baking biscuits, as evidence that PBL taught the wrong things. I shall henceforth remember her fondly as ‘rigorous Rachel’. In their defence, the TES at least shared quotes from some of the intervention schools. One of these schools that’s presumably been failing their Yr 7 students was Stanley Park High School. In an unfortunate disjuncture, this same school had just been awarded 2016 Secondary School of the Year by…the TES. You couldn’t make it up. Oh, wait, they just did.

In my attempts to get some of the above to read the original evaluators report, in full, before exercising their prejudices, I was accused of dismissing the evidence. I’m not. I’m the first to say that the evidence based for PBL is weak (though stronger than many claim, and the evaluators have done a good job in presenting the key messages from a literature review). Many people who see very positive impacts of PBL (in extraordinary schools like Expeditionary Learning, High Tech High and New Tech Network in the USA) are very anxious to see large-scale, reliable research emerge on the breadth of impact of PBL.

But, until we have that, can we stop hysterically distorting what little evidence we have? The rising popularity of PBL around the world has enthused and revitalised legions of classroom teachers. Until we’ve got some conclusive evidence that it’s not working, can we allow them to exercise their own professional judgement, please?

Related Posts

Also published on Medium.

Social tagging: Education Endowment Foundation > Innovation Unit > Nick Gibb > OFSTED > Project-Based Learning > TES

Excellent post, David. Thanks. You’re also right that you couldn’t make it up.

Mayflower Academy in Plymouth has this headline on its Performance page: “Mayflower Community Academy has received a special letter of praise from Schools Minister Nick Gibb.” It is for being among the 100 top performing schools in terms of the progress made by pupils between Key Stage 1 and Key Stage 2, between ages 7 to 11.

How is this achieved? Well you have guessed it: “Our bespoke and creative Academy curriculum is delivered through ‘Project Based Learning’ experiences.”

So, the ‘TES’ gives Stanley Park Secondary School of the Year. Nick Gibb writes in praise of a PBL school’s achievement. Ofsted consistently lauded the REAL Projects work in the trial schools (even when other aspects of the school were under pressure). Yet people would rather publicly celebrate a report so misrepresentative of the evidence that even the evaluation team are going to complain!

David, I very seldom respond to posts that I read, but after reading the complete study and your previous post as well as your post here I could not help myself. I not only concur with your analysis, but would take the critique further. The Summary concludes no definitive evidence and is extremely weak lending itself to be used as a position to denounce PBL.

Personally, I feel it was irresponsible for a study with so many flaws to have even been published. As a practicing practitioner and the Founding Principal who designed and ran one of the most successful 100% PBL schools in the United States for the last 9 years with “under represented students” as well as train teachers all over the world in PBL (China, UK, US, and soon to be Australia) with Think Global PBL Academies, I question the validity of this study all together.

As you pointed out they did not compare “apples to apples” for value added performance when looking at closing the achievement gap. This is a huge issue! Skimming over the essential 21st century skills the students gained appears irrelevant. I can almost guarantee those essential skills increased dramatically. For those that left the study as well as the PBL differences from teacher to teacher and school to school begs to the question if the teachers created standards based authentic student interest projects or were these canned projects. I also laughed at the comment that they saw no improvement in attendance. I admit to some ignorance on school attendance in the UK. We had significant raised attendance rates from students who previously missed school often. Over 9 years our HS attendance average was 96.5% often 97+% where the average HS attendance hovers around 92-94%. Our under represented students consistently out performed on State Exams, and in our 6 graduating classes thus far we had a 99.4% graduation rate with 100% of those accepted into College where 62% were first generation being the first in their family to ever go to college while many were the first in their family to graduate from HS! I know first hand the positive impact PBL has had on students and families not only at my campus, but others around the globe. If the President of the United States can see the significant student improvement in our PBL school and dedicate 300million dollar grant for others to replicate our practices and the US Secretary of Education can highlight our PBL school as a model school to reach under represented students I find it amusing and sad at the same time that educational leaders would jump on this to study to highlight the deficits of PBL.

I recently open another 100% PBL school and am seeing similar success results in only 5 months!

As someone who has participated in numerous case studies from George Washington University, University of Chicago, University of Texas, Dana Center, and others. I have found anyone can make numbers work the way they want. Being a standard bearer for educational transformation is not easy, but I can say over the last 11 years as a PBL guru those voices trying to negate PBL as a viable pedagogical shift for student achievement has declined and I believe will continue as more and more reliable studies take center stage. Thanks for the excellent post and the motivation to write. Former Founding Principal of Manor New Technology High School, Head PBL Potentialist; Advanced Reasoning In Education, and Founding Principal of Cedars International Next Generation High School

Steven, Thanks for commenting. The stats you provide are interesting, and consistent with other well-established schools in the US and, increasingly, in the UK and Australia. Those sorts of figures are just as valid forms of ‘evidence’ as RCT studies. In fact, I’d argue that, for teachers, they’re more influential. I think the more rigorous forms of PBL are relatively new to the UK, but people here still remember the laissez-faire, scaffold-less, form of PBL of the 1980s, and that was a disaster. Chains in the US like High Tech High and Expeditionary Learning have been doing this for some time (at least 9-10 years) and would confirm that it takes 3-5 years to really establish a whole-school PBL culture, and then the standardised results tend to be really impressive.

That said, PBL isn’t for all schools or all students, and it’s particularly difficult for schools that are in challenging circumstances. But it’s certainly not a ‘pedagogy of privilege’ as some are now suggesting – as your stats reinforce.