I spoke last week at an education conference on enterprise education. As invariably happens at these kinds of events, talk soon turned to the skills young people going to college will need. Since, in my experience, there is always a broad consensus expressed by academics and business leaders alike about the need for the ‘C’ skills (collaboration, creativity, critical thinking – only political advisors and education ministers seem to disagree with this consensus), the next question which invariably follows is, what kind of curricula will best equip kids for the future?

I spoke last week at an education conference on enterprise education. As invariably happens at these kinds of events, talk soon turned to the skills young people going to college will need. Since, in my experience, there is always a broad consensus expressed by academics and business leaders alike about the need for the ‘C’ skills (collaboration, creativity, critical thinking – only political advisors and education ministers seem to disagree with this consensus), the next question which invariably follows is, what kind of curricula will best equip kids for the future?

It’s hard to think of another sphere of human endeavour in which the structural framing device has changed so little over hundreds of years. Here’s an algebra test paper from 1869:

Seem familiar?

Curriculum reviews seem to come around as regularly as elections (an odd coincidence) but they essentially revise existing subjects – it’s rare that an entirely new subject appears. Which is why it was particularly noteworthy that UK primary and secondary schools this month introduced a new subject: computer programming. Let’s overlook the fact that it took Google’s Eric Schmidt to embarrass policy makers into re-thinking ICT, beyond learning how to use Microsoft Office, and concentrate on the positives.

But let’s not stop there. We’re in a multi-disciplinary world, and if our kids are going to compete, the subjects they study aren’t as important as ways of thinking. The New York Times ran a feature last week-end on Bill Gates’ latest passion: the teaching of the cross-disciplinary ‘Big History’ curriculum. According to the piece, it seems as though Gates has become frustrated with the lack of enthusiasm for his support for previous ‘top-down’ initiatives, and with Big History is looking to see if it can scale from the roots in schools. If he was looking for an easier ride, he faces disappointment, as the article notes:

“Gates, who had hoped to avoid bureaucracy, found himself mired in it. “You’ve got to get a teacher in the history department and the science department — they have to be very serious about it, and they have to get their administrative staff to agree. And then you have to get it on the course schedule so kids can sign up,” he said. “So they have to decide, kind of in the spring or earlier, and those teachers have to spend a lot of that summer getting themselves ready for the thing.” He sighed.”

Welcome to our world, Bill.

Personally, I hope Big History succeeds, not least because it challenges the absurd construct of the world in discrete boxes. But why stop there? Let’s see more examples of schools introducing disciplines and ways of thinking that our kids will put to good use later in their lives (unlike algebra). One pathfinder I visited recently is the Australian Science & Mathematics School in Adelaide. Interestingly, ASMS is a senior secondary school (so has more freedom with its curriculum) and has very strong links with Flinders University – it’s based on their campus. So, it has a better perspective than most on what colleges are actually looking for in tomorrow’s applicants.

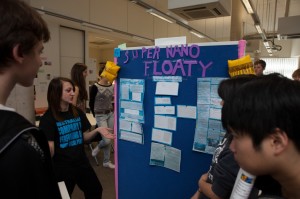

It’s heartening, therefore, to see their ‘central studies’ programme for Years 10 and 11: Nanotechnology, Biotechnology, Reasoning and Relationships, Sustainable Futures, The Earth & The Cosmos. We need more of these future-focussed, relevant courses.

In OPEN I case studied the School for Communication Arts 2.0 and their highly innovative ‘curriculum wiki’. This ensures that SCA 2.0 reflects the latest needs of the communications industry. If there’s a new way of doing things starting to emerge, someone – anyone – will suggest a new module on the public wiki, and then a course will be designed.

So, what new curriculum offering has your school introduced? How are you preparing students to understand the world as it is going to be, rather than as it was?