2014 is likely to see greater call for ‘stricter accountability’ for all kinds of public and private services. We seem to feel reassured if, say, doctors, or hedge fund traders are made more accountable for their actions. It’s entirely understandable that we should feel this way, but the reality is that trust is not the same thing as accountability – and each generate different reactions from those in whom we trust/make accountable.

2014 is likely to see greater call for ‘stricter accountability’ for all kinds of public and private services. We seem to feel reassured if, say, doctors, or hedge fund traders are made more accountable for their actions. It’s entirely understandable that we should feel this way, but the reality is that trust is not the same thing as accountability – and each generate different reactions from those in whom we trust/make accountable.

Curiously, while we may be disinclined to trust professionals, on a personal level, we’re trusting each other more than we’ve done for a while. Here’s an extract from OPEN: How We’ll Work, Live And Learn In The Future which examines a feature of accountability that I think we often overlook: the more accountable you make people, the less they’ll feel trusted, the more tempted they’ll feel to game the system, and the less chance you’ll have of ever getting that trust back. We only do our best work when we feel trusted, so we give up on trust at our peril.

“In recent years we’ve seen a loss of trust in many of our main pillars of contemporary life – banks, media, politicians and the police, to name just a few. At the same time, however, we’ve seen a rediscovery of trust in each other. Now, I don’t want to be naive about this: I know there are scammers, spammers, fraudsters and hoaxers to be found all over the internet. But the remarkable thing is how services that rely on user trust have gained in popularity over the past 10 years.

In ourselves we trust

If memory allows, try to recall the first time you won an eBay auction. Did you doubt that you would ever receive the item, after paying for it? I know that I did. Now, however, we buy and sell without a second thought, and with some justification, since fewer than 1% of eBay purchases result in fraud.

Even more remarkable is the growth of a site like Couchsurfing.com where hosts in a city offer free accommodation to visitors. Despite being conditioned by a media which, a decade ago, would have classed such an act as ‘asking for trouble’, there has been a growing acceptance that offering your couch to a foreign guest isn’t just an act of kindness – the host also benefits from the cultural insights gained.

Couchsurfing isn’t a ‘something for something’ service – only around 12% of friendships are reciprocated – but there is a generalised reciprocity, passing acts of generosity forward. In less than seven years Couchsurfing has built a membership of over 3 million people around the world, with abuse of trust incidence microscopically low.

The trust we place in such interactions works because of the service providers ‘reputation system’. eBay buyers and sellers understand the importance of positive feedback (fewer than 5% of auctions attract negative feedback), and because there are risks to personal safety, Couchsurfing has a set of identity verifications, friendship ratings and ‘vouch for’ mechanisms, in addition to feedback ratings.

The rise of reputation-based, social sites confirms what we knew all along – that we want people to think well of us, and that we want to trust our fellow citizens – it’s simply that, up until now, we never had the tools to show what we could do for each other, given the chance. A spirit that was previously only seen between neighbours now spans the globe.

Trust in Business

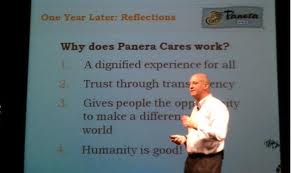

Whilst valuing trust may seem like a natural fit for the social space, it has always been a harder sell in the corporate world. Ron Shaich had built the Panera Bread Company into one of the biggest bakery brands in America, but was curious to see if trust made business, as well as social, sense. In May 2010 he opened the Panera Cares Community Cafe in Colorado. There are no prices in the cafe, and no cash registers. People put what they can afford into a donations box, (thus preserving everyone’s dignity) and if they can’t afford anything they volunteer an hour or so of their time.

Whilst valuing trust may seem like a natural fit for the social space, it has always been a harder sell in the corporate world. Ron Shaich had built the Panera Bread Company into one of the biggest bakery brands in America, but was curious to see if trust made business, as well as social, sense. In May 2010 he opened the Panera Cares Community Cafe in Colorado. There are no prices in the cafe, and no cash registers. People put what they can afford into a donations box, (thus preserving everyone’s dignity) and if they can’t afford anything they volunteer an hour or so of their time.

As a social experiment, it worked. On average, 20% of people pay more than the normal selling price, because they know they are supporting the 20% who pay a little less. And because running costs are low, thanks to the volunteers, the cafe is thriving. Shaich’s plan is to open four more community cafes per year, on a not-for-profit basis (but hopefully not-for-loss either).

As a social experiment, it worked. On average, 20% of people pay more than the normal selling price, because they know they are supporting the 20% who pay a little less. And because running costs are low, thanks to the volunteers, the cafe is thriving. Shaich’s plan is to open four more community cafes per year, on a not-for-profit basis (but hopefully not-for-loss either).

The importance of trust in how corporations create an effective working environment could not be more important, according to the people who judge it. The Great Place To Work Institute has 25 years of research which shows, year-on-year, that when employees are asked ‘what’s the most important reason for staying here? it isn’t the subsidised lunches, or other perks: it’s trust. Moreover, Great Place to Work have noted a direct correlation between the level to which employees feel trusted by their bosses, and the profit made by the company.

When Trust Goes Missing

Trust is often linked to accountability through the process of target setting in both private and public sectors. In this context, we are told that accountability helps reinforce trust. I don’t believe this has ever been the case. Instead, accountability is usually what’s left after trust has been removed. The visionary management consultant, W.E Deming, once described attempts to make everyone accountable as ‘ridiculous’, claiming that ‘whenever there is fear, you will get wrong figures’.

The erosion of trust in public school systems has had catastrophic consequences, and will take decades to put right. As we’ve seen, attempts to make schools ‘more accountable’ for their test scores leave teachers torn between what psychologist Barry Schwartz calls ‘doing the right thing and doing the required thing’. The right thing is to teach students through personalised, flexible methods, according to their needs, interests and aspirations; the required thing is to ‘turnaround’ test scores, by ‘teaching to the test’ or, worse, ‘gaming’ the system.

Successive US federal administrations have sought to improve school standards through high accountability. The pressure this puts upon schools at risk of closure and teachers – with test scores linked to pay rates – is intense. During 2011/12 a series of allegations emerged of inner-city schools in New York, Washington DC, Atlanta and Philadelphia ‘cheating’ on student test scores in order to hit accountability targets. Undoubtedly a case of fear producing wrong figures.

The result, of doing the required thing, above the right thing, is what Schwartz describes as a ‘de-moral-ised’ profession. The double tragedy is that, in addition to the pressure put on teachers – 50% of new teachers in the US leave the profession within their first five years – there’s growing evidence that the over-reliance on standardised testing fails to improve academic learning anyway.

The US National Research Council’s Committee on Incentives and Test-Based Accountability recently produced a damning report showing that increasing student performance on high stakes tests not only did not increase student achievement in other measures of academic ability, but also had a detrimental effect on graduation rates. Other incentives, including linking teacher pay to exam results, or paying students to pass exams produced similarly disappointing results.

Contrast this culture of distrust, deception and demoralisation with the Finnish schools system. For over a decade, Finland has consistently topped the OECD’s international comparisons on student’s achievements in reading, writing, maths and sciences. Politicians and education experts have speculated on the reasons behind Finland’s success.

Pasi Sahlberg, Director of Finland’s Centre for International Mobility is in no doubt. He defines the ‘new culture’, which transformed the relationship between government and schools in the 1990s, in this way: “Basic to this new culture is the cultivation of trust between education authorities and schools. Such trust as we then witnessed made reform not only sustainable, but also owned by teachers.”

It seems that we could learn a lot about trust from Nordic educators. In 2009 students in Danish schools were allowed to access the internet during final examinations. They could use any sites, but were not allowed to message or email each other. The Danish government argued, with devastating logic that if the internet is so much a part of daily life, it should be included in classrooms and exams. One of the teachers leading the pilot was asked by the BBC what precautions were put in place to prevent cheating. ‘The main precaution’, she replied, ‘is that we trust them.’

You can’t say fairer than that, can you?”

Interesting. I suspect part of the problem is our “rational” decision making process, the same process that lawyers use to obfuscate matters in court and MBAs use to justify legal but unsustainable biz practices. When you focus on the person and the story, take in the user perspective, our empathetic selves become engaged and that is where our honesty and morality reside.

Fascinating article. Speaks to my heart and confirms my experience in the workplace. I know that your focus is education and it seems that there is a lot to do to re-establish trust in the school system. Still, I would like to encourage you to present this article (or one with more of a business focus) to The Guardian Sustainable Business Section, Forbes or Harvard Business Review.

The erosion of trust in business systems has equally catastrophic consequences and looking at the tasks ahead which need to be tackled, business is critical and cannot afford to lack trust.

Btw. Some personal experience with business leaders makes me wonder whether they trust themselves. Is this something you are qualified/experienced to write about?

Yes!!!

This is a quite brilliant article David. I realise it is aimed at education, but the demonstrably lack of trust (and, I would argue, professional respect) within the arts/culture and specifically funding sector is resulting in an accountability driven demand for information that defies common sense; a repetitive and wholly meaningless request to establish time and again who you are, where you are from, what you do, sometimes six or seven times within the same application or interaction, and frequently from organisations with which you have worked for many many years. I don’t believe that the cost to the damage of the relationship has been properly factored in or calculated, and certainly the administrative expense of managing a relationship in this manner are unjustifiable.