It’s been a bad week for the high-stakes accountability advocates.

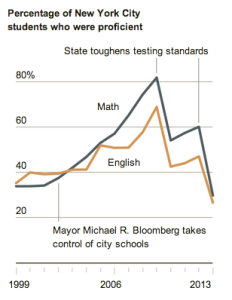

First, came the news that, in New York City, test scores for students in English and Math had fallen off a cliff. Some of this precipitous drop – from 47% to 26% in English, from 60% to 30% in Maths – was explained by a switch to the ‘tougher’ common core standards. But a halving of scores can’t simply be down to tougher exams.

The performance graph on the right is consistent with many other measures designed to ‘toughen up’ on standards. An immediate hike upwards – often the result of teachers having to work much harder, and the short-term impact of ‘drill-kill’ – is seen to be unsustainable. It would be fascinating to see a graph of disengagement laid over this one.

Mayor Bloomberg saw fit to describe the results as “very good news” (go figure), but the Principal from a school in Harlem was despondent. Seeing the scores for her disadvantaged students sink to below 10%, she said that she had no idea what to tell parents.

Meanwhile, in England, more good news emerged.

In an OECD comparison, literacy rates among England’s 16-24 yr olds have slipped – England now stands 22nd, out of 24 countries in that age range. Unlike almost all other countries, England has better literacy rates among 55-65 yr olds than their grandchildren. Many of these young people were forced to endure the (then) Labour Government’s ‘literacy hour’ when they were at school. Labour invested significantly in enforcing tougher approaches to literacy in the classroom, despite the howls of protest from teachers and authors (who argued that such de-contextualised teaching approaches were strangling kid’s love of literature).

Several illuminating letters appeared in The Guardian, in the wake of the report. Mary Midgeley wrote, ‘education now centres entirely upon how to pass exams..the aim is no longer to educate the child for life, but to keep the school out of trouble’; David Gribble argued that ‘ the fact that those aged between 55 and 65 have done better than those aged 19 to 24 shows that the comparatively free style of teaching in the despised 1960s was more successful than the formal systems that have been brought in since then.

Similarly, John Taylor Gatto has previously pointed out that literacy rates in Massachusetts were higher before the introduction of compulsory schooling, than after.

The political paucity of ideas on how to innovate to improve literacy and numeracy is depressing. Could we not at least revisit more holistic. more engaging, approaches to learning that were popular 40-50 years ago, and ask if we haven’t been on the wrong track for the past couple of decades? Simply cranking the handle harder, and getting teachers to ‘do more (of the same) and work harder’ isn’t working.

I fear, however, that ideology will trump objectivity yet again, and consideration of more ‘progressive’ approaches will be dismissed as going ‘soft’ on teachers. Ignoring the definition of insanity (doing the same thing over and over again, and expecting a different result), I fear that beatings will continue until test scores improve.

Link: OPEN: How We’ll Work Live and Learn In The Future is published by Crux Publishing, and available from Amazon