So, here are four ways (at least) that the Conservative education strategy Is aping White House rules:

- Keep telling lies, ignore evidence to the contrary. Schools minister Nick Gibb has consistently denied that recruitment – and retention – of teachers in schools in England is an issue. His manipulation of statistics looks like Sean Spicer has been doing the calculations. The reality, according to the TES, is that applications to teacher training programmes this year are down by a whopping 33%, and record numbers of teachers are leaving the profession. Analysts say that low-pay, excessive workloads, rock-bottom morale and increasing accountability all affect the numbers of people applying to teach, and the number of teachers still in the classroom after 5 years. It’s a crisis – but the government remains in denial. The latest novel tactic? Supporting Now Teach, the charity that seeks to talk ‘professionals’ out of retirement and into teaching. I know you might be thinking that teaching is a profession too, but apparently not. And, in the two years since being founded, Now Teach has had 50 graduates! Five-O! If this sounds familiar, you may recall Troops to Teachers, a scheme to fast-track military veterans into the classroom. Set up in 2016 with a £4.3m grant and an initial target of 2,000 applicants, the scheme graduated 28 teachers in 2016 (that’s only £153,571 a pop). So, 78 across both schemes more than compensates for the 34,910 teachers that left the profession in 2016 for reasons other than retirement. Doesn’t it?

- Value loyalty above experience. The government has, like Trump, preferred to surround itself with advisers and ‘tsars’ that are wholly unqualified to offer advice and tsaring, but are handsomely rewarded – either through promotions or substantial grants – for a particular form of ‘aggressive loyalty’. Government loyalist and all-round good-egg, Toby Young, (already Director of the New Schools Network) was last week chosen to be the Higher Education Student Tsar. Announcing his new job, the Department for Education falsely claimed that Young had held teaching posts at Harvard and Cambridge (he hadn’t, but see rule #1),It is as inept a decision as the appointment of Anthony Scaramucci as White House Communications Director – and likely to last about as long.

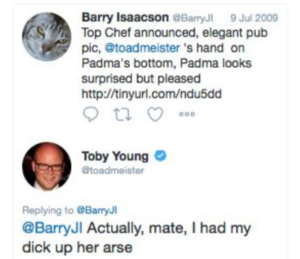

Character is for suckers. The most popular Secretary of State for Education in years, Justine Greening, is expected to lose her job in the Prime Minister’s cabinet reshuffle tomorrow. Meanwhile, self-confessed porn-addict Toby Young, universally criticised for his disgusting, misogynist Tweets over many years, is championed by Michael Gove and part-time Foreign Secretary/full-time BoBo the Clown stand-in, Boris Johnson. Johnson said that Young was the ‘ideal’ candidate, since he’d bring a ‘caustic wit’ to the job. (Apologies to anyone upset by the language used, but I thought I should include one of the 50,000 tweets Young has sought to furiously delete in the past few days, as an example of this caustic wit). Now, Greening is apparently taking the rap for the Tories failure to realise that education was seen by voters as a key issue at the last election (even though she wasn’t in post at the time). Young, meanwhile, blames the whole furore on the fact that he’s a Tory supporter, and not a believer in eugenics, or his fixation with women’s bodily parts. Theresa May has criticised Young, saying “I’m not at all impressed…if he continues to use that tone, he will no longer be in public office”. A Principal Skinner final warning from Mrs May then, but Mr Young, has (for the moment) mysteriously survived. Greening, however, is considered by May to be ‘patronising’ so she obviously has to go…..

Character is for suckers. The most popular Secretary of State for Education in years, Justine Greening, is expected to lose her job in the Prime Minister’s cabinet reshuffle tomorrow. Meanwhile, self-confessed porn-addict Toby Young, universally criticised for his disgusting, misogynist Tweets over many years, is championed by Michael Gove and part-time Foreign Secretary/full-time BoBo the Clown stand-in, Boris Johnson. Johnson said that Young was the ‘ideal’ candidate, since he’d bring a ‘caustic wit’ to the job. (Apologies to anyone upset by the language used, but I thought I should include one of the 50,000 tweets Young has sought to furiously delete in the past few days, as an example of this caustic wit). Now, Greening is apparently taking the rap for the Tories failure to realise that education was seen by voters as a key issue at the last election (even though she wasn’t in post at the time). Young, meanwhile, blames the whole furore on the fact that he’s a Tory supporter, and not a believer in eugenics, or his fixation with women’s bodily parts. Theresa May has criticised Young, saying “I’m not at all impressed…if he continues to use that tone, he will no longer be in public office”. A Principal Skinner final warning from Mrs May then, but Mr Young, has (for the moment) mysteriously survived. Greening, however, is considered by May to be ‘patronising’ so she obviously has to go…..- Believe (or Tweet) six impossible things before breakfast. Trump maintains that he’s passed more legislation in his first year than any previous incumbent (fact-check: the opposite is actually the case) He has redefined contradictory policy-making – easy to do when you promulgate ‘alternative facts’, and your two closest advisers – Jared and Ivanka – admit to being Democrats. But the UK government are giving him a close run for his Russian money……In what may prove to be her final policy idea, Justine Greening launched the ‘Unlocking Talent, Fulfilling Potential’ plan in December 2017. The plan had four laudable ambitions: Close the language/literacy gap; Close the attainment gap; Offer real choice at post-16; Raise career aspirations. During the same month, the government saw the mass resignation of its Social Mobility Commission and its prominent Chair, Alan Milburn. Adopting Trumpian spin tactics, the government said he was going to be ‘stepped down’ anyway. Since almost losing the last election, the government has cut funding to schools, further and adult education. Child poverty rates are now 30%. And the attainment gap is widening: recently released data shows the impact of successive austerity cuts – the gap in numeracy, literacy and writing has grown ever wider between well-off students and those receiving free school meals, and better-off students are now twice as likely to be offered a university place than their poorer counterparts. Just as Trump’s recent massive tax-cut for the super-wealthy is his fulfillment of his pledge to remember the forgotten men and women of middle America, so the widening educational gap makes a sham of Theresa May’s incoming pledge to fight ‘burning injustice’ and ‘make Britain a country that works not for a privileged few, but for every one of us.’

The Prime Minister this morning repeated her insistence that Donald Trump would pay a visit to the UK in 2018. I’ll be joining the many UK citizens who will want to give him a welcome he will never forget. But amid the inevitable cacophony, we’d do well to remember that the playbook that got him into power, now appears to be required reading for a government and a Prime Minister desperate to cling to what little power they now retain. Welcome to the moral wasteland of British governance.

]]> The past few days have seen the opposite (if not equal) reaction to the recent emergence of the #EducationForward campaign. With scant regard for factual accuracy, various bloggers and tweeters (since they crave attention I’ll anonymise them for now) have attempted to summarise the Education Forward book, without the tiresome task of actually reading it. One, describing #EducationForward as ‘Education Backward’ (witty), linked EF to Class Action, the recently created magazine ‘by teachers for teachers’ (wrong). Others questioned how EF is funded (it isn’t). But the biggest (though I suspect knowing) misconception has been to cast Education Forward as promulgating ‘the vision of progressive education”.

The past few days have seen the opposite (if not equal) reaction to the recent emergence of the #EducationForward campaign. With scant regard for factual accuracy, various bloggers and tweeters (since they crave attention I’ll anonymise them for now) have attempted to summarise the Education Forward book, without the tiresome task of actually reading it. One, describing #EducationForward as ‘Education Backward’ (witty), linked EF to Class Action, the recently created magazine ‘by teachers for teachers’ (wrong). Others questioned how EF is funded (it isn’t). But the biggest (though I suspect knowing) misconception has been to cast Education Forward as promulgating ‘the vision of progressive education”.

If these bloggers had actually bothered to read the book, or watched Sir Ken Robinson’s opening to the recent conference, they would have seen repeated criticisms of the polarisation of education into Traditionalists and Progressives. So, only someone trying to pick a fight would deliberately cast the movement as one of the poles it is consciously avoiding. Education Forward’s objective is simply to change the conversation away from the same tired polarities (direct instruction vs discovery learning, academies vs comprehensives, etc) toward a much-needed discussion as to what kind of education system will be needed to enable young people to thrive in the future.

The people who attended the conference were talking about the need to adopt any teaching strategies that will help kids become more literate and numerate, globally aware, compassionate and curious, and equipped with the non-cognitive ‘soft’ skills that this week’s Education Policy Institute report argued are being neglected in the UK. One of the headteachers who spoke at the event was Mark Moorhouse, Headteacher at Matthew Moss High School in Rochdale. Mark talked about the school’s D6 initiative – recently praised by the government in its 2017 Parliamentary Review. I first observed D6, shortly after its introduction in 2014, and blogged about it here. I’ve just come back from a further visit, and it’s great to see that this non-ideological experiment now has clear evidence of its effectiveness.

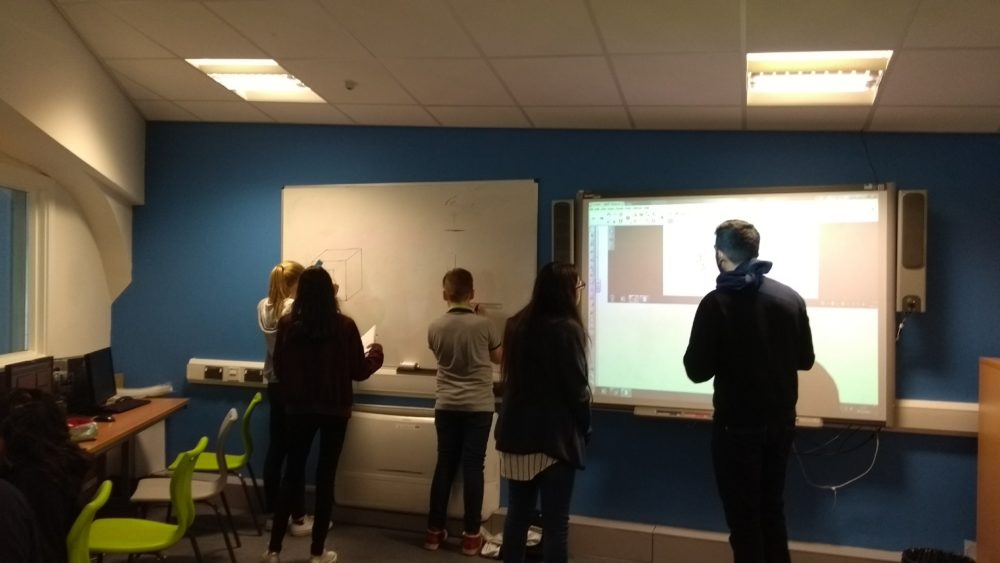

D6 operates on a Saturday morning and is a voluntary peer-to-peer learning experiment. Teachers are in attendance, but not in classrooms – they make tea for students and catch up on their marking. There are learning ‘coaches’ – students from the local sixth-form college, who are there to support learners – though some students prefer to work on their own. The content being studied is entirely determined by each group of around 3-6 students, so it’s impossible for the coaches to prepare lectures or worksheets in advance. Today was a relatively quiet day – just over 100 students turned up, largely because a new group of coaches are being recruited. Despite that, two floors of the school were filled with students, deeply engaged, and in charge of, their learning. With so much freedom one might expect to see students kicking a football around or playing video games. Almost all of the students I saw today were grappling with maths, chemistry or science problems. The school serves a large Asian community, and Rochdale is an area of high deprivation. I saw one group of white working-class boys (the so-called ‘hard to reach’) jubilant that they’d finally cracked percentages and overheard another say “I think I’m getting the hang of maths now” – the level of student agency was palpable.

But, here’s the thing: the actual pedagogy being deployed was often classic note-taking, demonstration and explanation stuff. On Monday, many of the Year 7s will be doing projects, some of the Year 8s will be getting a history lecture, while some of the Year 11s may be doing test prep – and there is no conflict. Only in the confrontational minds of some binary edu-tweeters is the question ‘which side are you on?’ even worth considering: for these kids, it’s all just learning. But Matthew Moss High School is future-facing, in so far as it passionately believes that a love of learning will be vital to their students’ prospects, because the future demands that we will all have to learn, unlearn, and re-learn throughout our lives. So, student agency over their learning is paramount.

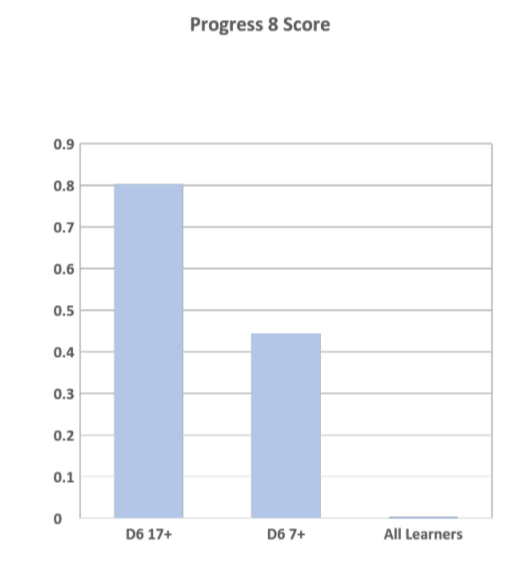

There are plenty of teachers that dismiss experiments like D6, arguing that research (they always seem to wheel out a single cognitive load study) ‘proves’ that novice learners need fully guided instruction and that ‘students are not good at making choices that optimise their learning’. Well, the students at D6 would beg to differ. Here’s the comparative test scores from last year’s D6 cohort who had attended 7 sessions, or more than 17 sessions, last year (overseas readers, please don’t ask me to explain how progress 8 scores work in England!):

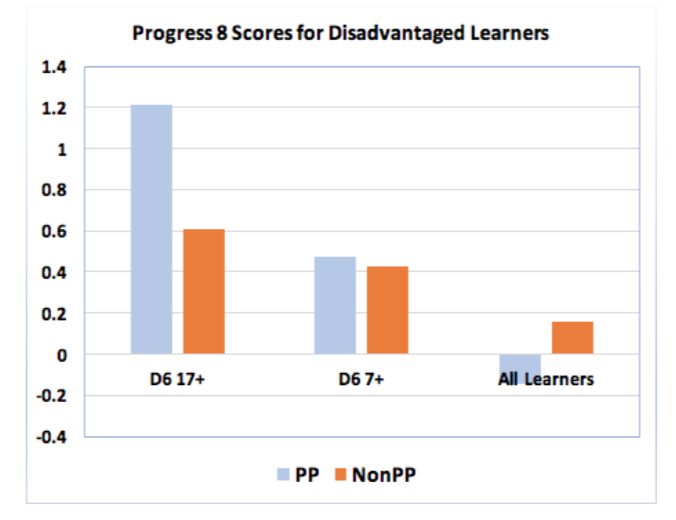

There is also a minority belief that anything other than direct explicit instruction, delivered by an expert to novice, will disproportionately penalise students from low-income backgrounds. Matthew Moss have analysed the impact of D6 upon students attracting additional ‘pupil premium’ funding (those in receipt of free lunches). Here, the figures are particularly striking:

So, the introduction of peer-to-peer learning is having a remarkable impact upon test scores, learner confidence, and learner agency – especially among students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Education Forward wants parents, business leaders and educators to know that there are other models of instruction – neither ‘traditional’ nor ‘progressive’ but a combination of the two (if indeed one can categorise pedagogies as lazily as that) – that don’t present either/or scenarios. They can deliver good test scores and equip learners with the self-sustaining dispositions they’ll need throughout their lives. (It seems to be only in the UK that we have this obsession with these sterile arguments – the rest of the world’s educators must think we’re still in the 20th century.)

I’d urge educators to visit Matthew Moss High School to see D6 in action.

I’d urge everyone not to be drawn into pointless polarising debates on pedagogy, but instead to ask ‘how do we need to change our approach to education, in light of the enormous, disruptive changes that we’re facing?’

And I’d urge you to look at Education Forward’s 10 goals of future-focused education and, if you agree, show your support.

]]>

Mark Vickers-Willis , Dean of Middle School Students Welcomes our group

Days 4 & 5 of our study tour of future-focused schools took in three very different schools (for details of previous schools visited, see the last blog post).

Our first stop was New Roads School, a K-12 school, in Santa Monica. As the inspirational Principal Luthern Williams explained, New Roads is unique: an independent school entirely committed to social equity. In practice, this means that parents who can afford their fees know that 50% of those fees enable kids from under-privileged areas of Los Angeles to attend. You might think with such a disparity of backgrounds there’d be two distinct sets of students. In reality, it’s impossible to spot which students are on scholarships and which aren’t.

The four ‘pillars’ of New Roads – Social Justice, Environmental Stewardship, Diversity and Academic Excellence – are evident in every conversation, every piece of student work. Being located in Santa Monica they are, as Luthern put it, ‘surrounded by companies that are shaping the modern world’: new media, robotics, games developers and software developers abound, and New Roads makes full use of them.

When you forgo half of your income to ensure you achieve social, ethnic and racial diversity, then it’s not surprising to see that New Roads classrooms are, well, basic. But that doesn’t matter, because our group were consistent with other visitors to New Roads in being moved to tears by what Luthern describes as unashamed idealism. It’s hard to accurately dissect how this school works – the pedagogy that we saw wasn’t anything ground-breaking, but their students are astonishing. Their teachers described them variously as “diversity natives” and “global bridge-builders”, powerful advocates of a private school with a public purpose.

The highlight of our visit was a discussion with student ambassadors in the Steven Spielberg theatre (yes, he sent his kids there). They clearly demonstrated – not for the first time on our tour – that if you give students voice and choice, they will reward freedom with great responsibility. Students are taught, largely, by stage not age, and at high school are offered over sixty electives. In many schools such options might lead to a kind of paralysis of choice, but these students utilise this open curriculum to to allow them to find themselves (in the practical sense). One student praised the curriculum, saying “Here, I can be whoever I want to be” (at this moment that looks likely to be a forensic scientist). Another reflected on the personal responsibility that comes with a student-driven curriculum, saying “ If you’re open about where you’re struggling, or where you’re having difficulties, then help is available, but it’s your job to make the move”.

Luthern Williams shared research that shows that diversity isn’t just good for student’s empathy and compassion – it improves cognition too. This is a school where students are valued as equal members of a learning community, their weekly ‘Town Hall’ meetings often identify social and political issues that students feel strongly about – and then they plan action. So, the day before we arrived, the high school students marched in the streets surrounding the school in support of the US ‘dreamers’. Some students, however, felt uncomfortable, and their right not to take part was supported by their teachers. In a class that I witnessed, students were discussing possible links between violence and video games. Some schools might not want students to be discussing current political issues, but New Roads are explicit in their belief that schools have a key role to play in pursuit of the US founding father’s dream of ‘a more perfect union’. Unashamedly idealistic, New Roads is a brilliant example of how academic excellence can be driven by diversity and that perhaps the key purpose of a school is, to paraphrase Luthern Williams, ‘to give students the tools to make sense of the world on their terms, not ours’. I wish every dispirited teacher who believes that teachers make decisions about students’ learning because ‘they don’t know what they don’t know’ could spend a week in New Roads School.

The following day our group visited two sister schools in the urban heart of San Diego. Set up as a single ‘charter’ entity, the two schools (Urban Discovery Academy at K-8 and Ideate High Academy) represent the application of a start-up culture to the persistent problem of public schooling in the United States. Chris Wakefield, the principal of Ideate, showed us alarming statistics on the disparity of wealth in a city like San Diego. Since their schools only get paid on the days that students attend, the lower attendance rates invariably seen in inner-city schools mean that such schools have progressively been starved of money, and have become ever more socially unequal. In an attempt the halt this decline, charter schools are invited to bring more innovation into public education.

Whatever one thinks of charters (in the UK, their equivalent is academies), they certainly don’t get any favours – there are good and bad examples to be found, but the bad ones don’t last long, with charter renewal coming along every five years. As the name suggests, Ideate High Academy have Design Thinking at the heart of their curriculum and early results (they’re only in their second year) are showing that student’s academic results are promising. However, they have another two years before their building is ready and the temporary premises they’re currently using are challenging to say the least – a recent outbreak of hepatitis A among the homeless community that inhabit the streets surrounding Ideate meant that hand sanitisers were everywhere. It doesn’t take more than a few minutes to see the scale of the challenge facing Chris. However, he only has to see the progress that his sister school, Urban Discovery Academy, has made to have cause for optimism.

Urban Discovery have come through the growing pains of a start-up, have a brand new building, and a waiting-list of students to confirm that they’re doing something right. The building itself is one of the most colourful I’ve seen, and the students seemed delighted with their new home. The ‘content rich’ dominance in recent years in the US definitely seems to have shifted in many urban charter schools and at UDA the curriculum is part STEAM, part project-based – in many ways a restoration of the liberal arts tradition that served US tertiary education so well. As any tech entrepreneur will tell you, starting-up is the hardest part of any project. New Roads School was also a start-up twenty years ago, and they’re now in a position at the forefront of change. We need more private schools with a public purpose. We also need people like Chris Wakefield with vision, boundless energy, and a determination to get over the challenges of start-up, to show that future-focused schools can meet the need for innovation and social purpose in our schools.

Urban Discovery have come through the growing pains of a start-up, have a brand new building, and a waiting-list of students to confirm that they’re doing something right. The building itself is one of the most colourful I’ve seen, and the students seemed delighted with their new home. The ‘content rich’ dominance in recent years in the US definitely seems to have shifted in many urban charter schools and at UDA the curriculum is part STEAM, part project-based – in many ways a restoration of the liberal arts tradition that served US tertiary education so well. As any tech entrepreneur will tell you, starting-up is the hardest part of any project. New Roads School was also a start-up twenty years ago, and they’re now in a position at the forefront of change. We need more private schools with a public purpose. We also need people like Chris Wakefield with vision, boundless energy, and a determination to get over the challenges of start-up, to show that future-focused schools can meet the need for innovation and social purpose in our schools.

Is it a school or a great coffee house?

For the past three days, I’ve been taking a group of school leaders and teachers around some of the most innovative schools in the United States. We curated the visit to concentrate upon Silicon Valley, primarily because the startup culture and spirit of enterprise that has made this region boom, has impacted upon the re-design of education – so long as you know where to look. It’s also a place where the jobs of the future are being created in the knowledge economy.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, this spirit of innovation is found more commonly in independent schools. I wish that were not the case, but public schools here face many of the same constraints that curtail risk-taking in public schools everywhere. Later in the study tour, we’ll be looking at charter schools – where there is greater accountability than in the private sector.

The three schools we’ve visited – Monte Vista Christian School, near Watsonville (about an hour west of San Jose), Nueva School, San Mateo (near Palo Alto) and Alt School in San Francisco – have shown extraordinary generosity with the time and a genuine interest in what our international group of educators thought about their respective missions. As a result, the learning has already been immense.

Rather than give a school-by-school breakdown, it makes more sense to look for commonalities and trends. Here’s what has struck me so far:

Use of space: all three schools get the idea that kids can only learn well if they are comfortable – physically, emotionally and spiritually. Monte Vista is set in spectacular countryside. Despite its proximity to Silicon Valley, this is farming country, between the mountains and the sea. But Monte Vista is also in the throes of turning what were very traditional classrooms into spaces that feel more like family living rooms. Similarly, Nueva’s elementary and middle schools are set in beautiful grounds, with accommodation that’s a mix of the old and the

3rd Graders at Nueva discuss Culture – yes, 3rd graders…….

new. This has clearly had a profound effect on both Monte Vista and Nueva. Both have been around in excess of 50 years, and recognise their tradition and founding visions, but they’re not enslaved to them. Both were radical innovations in their creation, and they’re determined to keep innovating.

Ownership of learning : all three schools believe that students need to own their learning for it to prepare them for a lifetime of learning. At Nueva’s Upper School, half of the senior student’s schedule is made up of electives. And the choice is truly impressive: Social Justice, Experimental Biology, Drug Design, Machine Learning, Modern Film Making, Cultures of Postmodernism, Neuroscience and many more. Nueva’s Upper School felt more like a university than a school, and some students can gain university credit – not least because some of the student research work is at least undergraduate standard. Some students have been working on CRISPR gene editing, while others are carrying out original research into the P53 tumour suppressor protein. Nueva is a selective school, but the bar isn’t set at prohibitively high levels, and their students are doing really important research work, way in advance of standard common core standards.

Our educators meet in Monte Vista’s ‘library’

Alt-School essentially exists to shift learning from being teacher-centric to learner-centric. Founded by Max Ventilla – former senior product manager and head of personalisation at Google – it is a stunning example of the startup entrepreneurial culture of Silicon Valley, both in its ambition and its seriousness. Alt-School have 7 lab schools that work closely with over 50 tech engineers, all committed to truly personalising the student experience. It’s a ‘for-profit’ that is determined to have social impact in making learning competency-based, owned by students and embedded in a network of supportive relationships with parents and community. We saw the first beta version of the hugely impressive software platform that will be launched next year. It provides a 360 approach to a student’s learning: curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. As you’d expect from a former Googler, every is open, so parents are critically involved. But it is designed to enable the student to work out what they need to know, and how to find it, using the ‘playlist’ concept. Max is the brains behind the Google sidebar recommendations/ads tailored specifically to your previous interactions, so you can expect a learning management platform that is far more sophisticated than anything we’ve seen before, and one which will take full advantage of the network effect. When large numbers of students are using this platform (and Alt-School is soon to make its system widely available to schools in the public sector) we will have the most powerful dataset of how students learn, but also what pedagogies should be used in a range of contexts and conditions. It will make current ‘what works’ methodologies look primitive in comparison.

Making time and space for innovation: all three schools firm

ly believe in modelling the collaboration we look to see in student work, through adult learning. Monte Vista have a new principal, Mitch Salerno, who is building a real community of adult learners. So, our visit was seen less as a ‘show-and-tell’ and more of a great opportunity to learn from the Romanian, Indian, Australian and British educators in our group. Equally, we visited Nueva a couple of weeks before their conference around innovation in learning – run largely by parents. While we were visiting Nueva, Scott Swaaley was taking parents around their i-lab spaces – these are extraordinary places (it diminishes them to describe them as merely ‘makerspaces’) originally created by David Kelley of Ideo. So, design thinking infuses throughout their practice, fuelled by their close association with Stanford’s ‘d-school’ lab.

In order to stay fresh, Nueva hire in subject specialists as well as accredited teachers. They believe that, if you’re future-focussed, it’s easier to train teaching knowledge than subject expertise. So, they have a sophisticated internal training programme, and make the time for it through reduced teaching loads.

Similarly, Alt-School is a living laboratory to study teaching and learning behaviours and impacts. Every interaction between teacher and student is videoed and analysed. It then ad

ds to the growing database they have that informs continuous conscious performance improvement.

These are just three ways that innovative schools in California are looking to the future needs of students and in building systems at scale. I could talk about their attitudes towards building self-sufficiency, compassion, social purpose in their students, but that can wait for a later post.

These three schools are remarkable examples of what can happen when you abandon false restrictions of what students are capable of achieving. They are all fee-paying, independent schools, but there’s much to learn, and much to be applied in the public sector, from what they are doing.

The next post will examine schools that straddle private and public sector divides.

]]>

How well are nations preparing their young people for the future? In the face of unprecedented challenges, it’s fascinating to see how education debates, and government policies differ around the world. I’m fortunate enough to be able to work in a number of countries and, as I’ve been editing a book* specifically dealing with this issue, it’s very much at the forefront of my thinking.

How well are nations preparing their young people for the future? In the face of unprecedented challenges, it’s fascinating to see how education debates, and government policies differ around the world. I’m fortunate enough to be able to work in a number of countries and, as I’ve been editing a book* specifically dealing with this issue, it’s very much at the forefront of my thinking.

But I’m far from alone: the film Most Likely To Succeed; the XQ Super School movement; the Richard Branson funded BigChange.org project – these are just a handful of examples, where serious thought is being dedicated to educational transformation. And that’s not to mention a slew of books published recently. As I’m currently in San Diego, I jumped at the chance to meet with the author of one of them. Grant Lichtman’s new book is called Moving The Rock: Seven Levers We Can Press To Transform Education. It’s been described by Yong Zhao (himself an advocate of radical change) as ‘an inspiring call to action for all educators’. I’d agree with that assessment. Meeting Grant gave me a chance to understand where our respective countries sit in relation to what he describes as the three stages of transformation: accepting why change is needed; identifying what those change would look like, and understanding how that transformation can be achieved, at scale.

Some countries – some would argue that New Zealand, Canada and Finland would be prime examples – seem to be well past the why, and are even at a point of agreement on the what. Even the most forward-thinking countries struggle with the how, but the how only becomes concrete once you’ve agreed on the why and what. Grant asked for my assessment of where the UK sits on that continuum. My personal view, and that of most of my co-authors, is that we’re still stuck on the why – at least in England (overseas readers may need to be reminded that each of the UK countries has its own education responsibilities and policies, and they’re beginning to differ quite radically). The political discourse around education reform in England is mainly centred on ‘standards and structures’: how to raise existing standards through various structural models. Very few politicians are talking about whether those standards are still relevant now, let alone in the next couple of decades. We’re still witnessing the same old turgid Twitter disagreements on whether ‘skills’ matter, or whether kids still need knowledge. Traditionalists ‘call out’ progressives (and vice-versa) for cherry-picking evidence, to support one extreme or the other. Advocates cite best practice – hardly anyone is talking about next practice. Let’s be clear: best practice is only going to address what’s worked in the past, not what we need to be ready for the future.

Speaking to Grant Lichtman confirmed something that Sir Ken Robinson had said to me at the end of last year: that in the United States, the argument, around the need for educational change, is largely over. Both Ken and Grant work with superintendents all over the continent. Their clear view is that there is a strong consensus that the historical obsession with standardised testing, driven by ‘PISA Hysteria’, has failed. Grant also feels that there is a pretty strong consensus on what should replace the drilling of a ‘knowledge-rich’ curriculum into young American minds – what has been described broadly as ‘deeper learning’. Now deeper learning comes in for a fair amount of criticism from traditionalists, but to me it’s simply a shorthand umbrella for a shift away from the superficial ‘covering’ of great chunks of curriculum, teaching to the test and assessing only the amount of knowledge that can be recalled in a timed test, in favour of greater depth of time on fewer curriculum areas, and applying that knowledge in authentic contexts. In short, it’s a response to the challenge that employers – particularly those in the rapidly expanding knowledge economies – are laying down: the world cares less about what you know, and more about what you can do with what you know.

If these two elements – the why and what – are taken as read, then the how is still formidable (because everything: curriculum, pedagogy and assessment, has to change) but it becomes achievable. So, we’re seeing initiatives spring up like the Mastery Transcript Consortium – a growing group of US high schools committed to finding an alternative to the narrow grading testimony that faces university admissions staff, one that reflects all of a student’s skills and dispositions.

So, if you believe that change is both urgent and inevitable, the question then becomes what does the future look like, and what can we do to move the conversation on?

For my part, I’m committed to trying to get as many people as possible to read our book, (and books like Grant’s) come to our event, and do what I can to get people in the UK to accept that we’ve been on the wrong track for a long time. Because if we can’t agree on the why, we’ll never get to the what and how.

If we want to see what the future looks like, I guess Silicon Valley is as good a place as any. The new economies, the growth jobs, all start there. It’s also the home of some of the most innovative schools in the world. So, I’m about to take a bunch of school leaders from several countries (though sadly none from the UK) on a 10-day tour of future-facing schools located in and around silicon valley. I’ll send as many postcards from the future as time allows, so watch this space.

* Education Forward: Moving Schools Into The Future is published by Crux Publishing on October 14th

]]>