The past few days have seen the opposite (if not equal) reaction to the recent emergence of the #EducationForward campaign. With scant regard for factual accuracy, various bloggers and tweeters (since they crave attention I’ll anonymise them for now) have attempted to summarise the Education Forward book, without the tiresome task of actually reading it. One, describing #EducationForward as ‘Education Backward’ (witty), linked EF to Class Action, the recently created magazine ‘by teachers for teachers’ (wrong). Others questioned how EF is funded (it isn’t). But the biggest (though I suspect knowing) misconception has been to cast Education Forward as promulgating ‘the vision of progressive education”.

The past few days have seen the opposite (if not equal) reaction to the recent emergence of the #EducationForward campaign. With scant regard for factual accuracy, various bloggers and tweeters (since they crave attention I’ll anonymise them for now) have attempted to summarise the Education Forward book, without the tiresome task of actually reading it. One, describing #EducationForward as ‘Education Backward’ (witty), linked EF to Class Action, the recently created magazine ‘by teachers for teachers’ (wrong). Others questioned how EF is funded (it isn’t). But the biggest (though I suspect knowing) misconception has been to cast Education Forward as promulgating ‘the vision of progressive education”.

If these bloggers had actually bothered to read the book, or watched Sir Ken Robinson’s opening to the recent conference, they would have seen repeated criticisms of the polarisation of education into Traditionalists and Progressives. So, only someone trying to pick a fight would deliberately cast the movement as one of the poles it is consciously avoiding. Education Forward’s objective is simply to change the conversation away from the same tired polarities (direct instruction vs discovery learning, academies vs comprehensives, etc) toward a much-needed discussion as to what kind of education system will be needed to enable young people to thrive in the future.

The people who attended the conference were talking about the need to adopt any teaching strategies that will help kids become more literate and numerate, globally aware, compassionate and curious, and equipped with the non-cognitive ‘soft’ skills that this week’s Education Policy Institute report argued are being neglected in the UK. One of the headteachers who spoke at the event was Mark Moorhouse, Headteacher at Matthew Moss High School in Rochdale. Mark talked about the school’s D6 initiative – recently praised by the government in its 2017 Parliamentary Review. I first observed D6, shortly after its introduction in 2014, and blogged about it here. I’ve just come back from a further visit, and it’s great to see that this non-ideological experiment now has clear evidence of its effectiveness.

D6 operates on a Saturday morning and is a voluntary peer-to-peer learning experiment. Teachers are in attendance, but not in classrooms – they make tea for students and catch up on their marking. There are learning ‘coaches’ – students from the local sixth-form college, who are there to support learners – though some students prefer to work on their own. The content being studied is entirely determined by each group of around 3-6 students, so it’s impossible for the coaches to prepare lectures or worksheets in advance. Today was a relatively quiet day – just over 100 students turned up, largely because a new group of coaches are being recruited. Despite that, two floors of the school were filled with students, deeply engaged, and in charge of, their learning. With so much freedom one might expect to see students kicking a football around or playing video games. Almost all of the students I saw today were grappling with maths, chemistry or science problems. The school serves a large Asian community, and Rochdale is an area of high deprivation. I saw one group of white working-class boys (the so-called ‘hard to reach’) jubilant that they’d finally cracked percentages and overheard another say “I think I’m getting the hang of maths now” – the level of student agency was palpable.

But, here’s the thing: the actual pedagogy being deployed was often classic note-taking, demonstration and explanation stuff. On Monday, many of the Year 7s will be doing projects, some of the Year 8s will be getting a history lecture, while some of the Year 11s may be doing test prep – and there is no conflict. Only in the confrontational minds of some binary edu-tweeters is the question ‘which side are you on?’ even worth considering: for these kids, it’s all just learning. But Matthew Moss High School is future-facing, in so far as it passionately believes that a love of learning will be vital to their students’ prospects, because the future demands that we will all have to learn, unlearn, and re-learn throughout our lives. So, student agency over their learning is paramount.

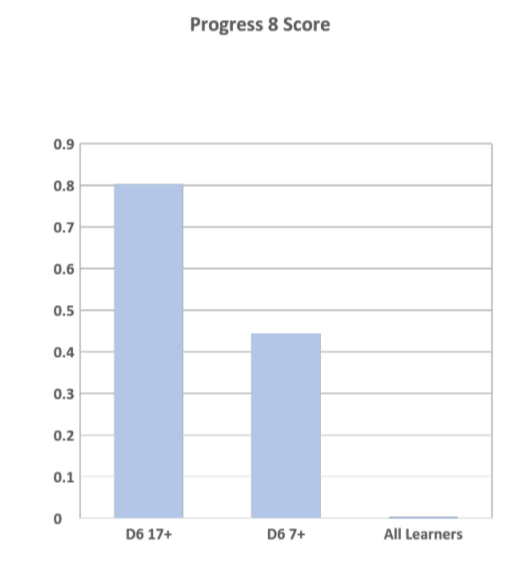

There are plenty of teachers that dismiss experiments like D6, arguing that research (they always seem to wheel out a single cognitive load study) ‘proves’ that novice learners need fully guided instruction and that ‘students are not good at making choices that optimise their learning’. Well, the students at D6 would beg to differ. Here’s the comparative test scores from last year’s D6 cohort who had attended 7 sessions, or more than 17 sessions, last year (overseas readers, please don’t ask me to explain how progress 8 scores work in England!):

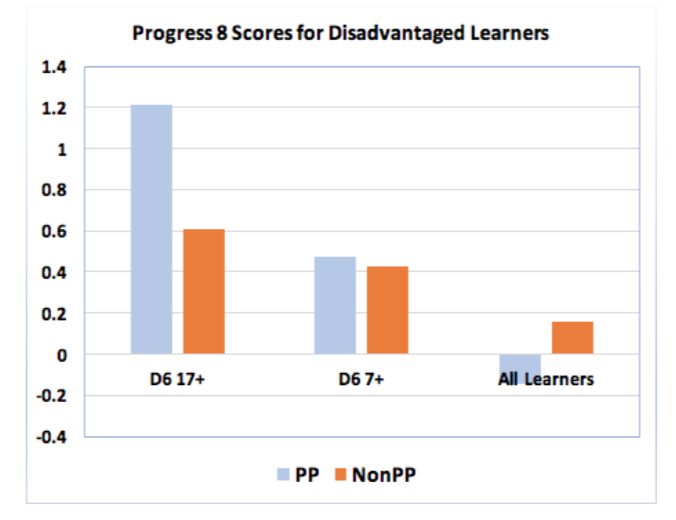

There is also a minority belief that anything other than direct explicit instruction, delivered by an expert to novice, will disproportionately penalise students from low-income backgrounds. Matthew Moss have analysed the impact of D6 upon students attracting additional ‘pupil premium’ funding (those in receipt of free lunches). Here, the figures are particularly striking:

So, the introduction of peer-to-peer learning is having a remarkable impact upon test scores, learner confidence, and learner agency – especially among students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Education Forward wants parents, business leaders and educators to know that there are other models of instruction – neither ‘traditional’ nor ‘progressive’ but a combination of the two (if indeed one can categorise pedagogies as lazily as that) – that don’t present either/or scenarios. They can deliver good test scores and equip learners with the self-sustaining dispositions they’ll need throughout their lives. (It seems to be only in the UK that we have this obsession with these sterile arguments – the rest of the world’s educators must think we’re still in the 20th century.)

I’d urge educators to visit Matthew Moss High School to see D6 in action.

I’d urge everyone not to be drawn into pointless polarising debates on pedagogy, but instead to ask ‘how do we need to change our approach to education, in light of the enormous, disruptive changes that we’re facing?’

And I’d urge you to look at Education Forward’s 10 goals of future-focused education and, if you agree, show your support.

]]>People are still around who lived through the Blitz of London during the Second World War, and I’ve always been proud of my country’s stoicism, so things will get back to normal with the minimum of fuss as they did after the 7/7 bombing. The reaction tonight from Donald Trump Jr was less restrained. He quoted an old interview with London Mayor (and Muslim) Sadiq Kahn: “You have to be kidding me?! Terror attacks are part of living in the big city, says London Mayor Sadiq Khan.” Well, actually, no. What Khan actually said was that we have to get used to the threat of terror attacks in big cities.

And we do. So, I was glad to see journalist Ciaran Jenkins report: “Khan is right. These things happen. We fight against them. But we don’t wildly over-react or let them change our way of life,” said Tom Coates, from London, adding that he had lived through IRA bombings and the 7/7 attacks on the London Underground.”

As I write, this story is unfolding, so it would be foolish to speculate – as Channel 4 catastrophically did – on the attacker’s identity. Whether Donald Trump Sr will use the attack to support his ‘Islamic Ban’ is not yet known, but if it turns out to be that, as in most terrorist attacks in the UK and USA, the perpetrator turns out to be a national citizen, then a travel ban isn’t going to make much difference.

Don’t get me wrong – for the people caught up in this horror, this was a terrible event. But looking for simplistic, knee-jerk solutions isn’t the way forward. The UK terrorist level was already at ‘severe’. Sadly, when an automobile becomes a lethal weapon there’s literally nothing security forces can do to prevent these kind of attacks.

So, what can we usefully do?

It seems to me that our focus needs to shift towards education as the best means of prevention. And I don’t mean the ‘de-radicalisation’ of returning ISIS freedom fighters – by then it’s too late. No, the process needs to start in schools, and in communities. The UK has followed many developed countries in recent years in moving away from an official policy of ‘multiculturalism’. Whatever one thinks of the supposed failings of multiculturalism, I’d like to ask: do we feel any safer as a result of this shift? Equally, do our children understand ‘the other’ in the ways that they used to do under the multicultural policy?

The sad thruth is that, in the narrowing of curricula, we have lost the space to talk about empathy, cultural awareness and the possible roots of terrorism, because we’re desperate to get our Numeracy and Literacy scores up. At the same time, our 24/7 news media only reinforces the notion that, if you’re a young British kid whose religion happens to be Muslim, your sense of belonging matters less than preserving the pillars of ‘Britishness’. It’s been striking to see how much of the TV coverage so far has been focussed upon the attack on the Palace of Westminster, (and by inference, democracy), at the expense of the fate of 40 people who happened to be walking across Westminster Bridge at the wrong time.

A woman lies injured after a shooting incident on Westminster Bridge in London, March 22, 2017. REUTERS/Toby Melville

Let me speak plainly. In the face of one man’s hatred, our ONLY response has to be love. For each other, and towards those we never speak to or socialise with.

In a strange coincidence, at lunchtime today I watched a news item about the anniversary of the bombing of Brussels airport. I was there just a few days ago, having worked at the Learning By Design conference at the International School of Brussels. What struck me so forcibly during that week-end was the emphasis upon two things: the UNESCO goals, and the benefits of internationalism. I was honoured to work with students from a range of countries who were creating socially purposeful global innovations that help bring us together, not drive us apart. And, throughout the whole event, there was a palpable, and visible, sense of love between delegates, teachers and students, who came from all over the planet to learn together and appreciate our differences.

The kinds of attacks we’re now witnessing in capital cities tend to come from ‘lone-wolfs’, inspired by copycat attacks, rather than orchestrated strategies from terrorist groups. So, if we can’t stop people from renting a car and driving it into a crowd of people, can we begin to see our schools as the best hope we have of preventing the sense of isolation that seems to fuel these lone wolf attacks?

And can we make tolerance, understanding, and love for ‘the other’, a cornerstone of our schools’ purpose?

]]>

Credit: S H Chambers

An earlier post of mine, on ‘what counts as evidence’, generated a healthy debate, and I thought I could leave the thorny problem of ‘what works’ in education for a while. Maybe lighten the mood with a blog about the all-out assault on the judiciary in post-Brexit Britain, or what’s an appropriate response to a Donald Trump presidency, something like that.

But the ‘evidence’ issue reared its contentious head again yesterday, November 4th, so The Donald might have to wait.

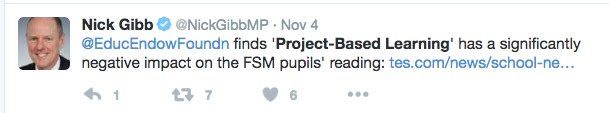

The flashpoint was the publishing of a report by the Educational Endowment Foundation (the UK equivalent of America’s What Works Clearinghouse) on the impact of Project-Based Learning on literacy and engagement.

The Times Educational Supplement was the first to claim “Exclusive: Project-based learning holds back poor pupils”. And the predictable social media onslaught ensued:

It soon became abundantly clear that hardly any of the Tweeters had bothered to read the actual report. In fact, I doubt very much that many of them had even gone beyond the abbreviated version of the TES article, the fuller version of which is only available on subscription So, before we go any further, please spend 5 minutes reading the EEF summary here. Better yet, read the full report.

The summary doesn’t get off to a great start with an bizarrely restrictive definition of PBL:

“Project Based Learning (PBL) is a pedagogical approach that seeks to provide Year 7 pupils with independent and group learning skills to meet both the needs of the Year 7 curriculum as well as support their learning in future stages of their education.”

But let’s move on to the gist of the conclusions:

“Adopting PBL had no clear impact on either literacy (as measured by the Progress in English assessment) or student engagement with school and learning.” Perhaps mildly surprising as PBL is often touted – by people like me – to enhance student engagement. Otherwise, nothing to see here.

“The impact evaluation indicated that PBL may have had a negative impact on the literacy attainment of pupils entitled to free school meals. However, as no negative impact was found for low-attaining pupils, considerable caution should be applied to this finding.”

I confess I’ve read this statement repeatedly, and I’m still none the wiser. Are free school meals students therefore not ‘low-attaining’? If considerable caution should be applied, why draw the conclusion in the first place?

This was the focus of the TES headline. Their journalist clearly read the full EEF report, but didn’t think it their responsibility to draw attention to the caveat ‘overall, the findings have low security…47% of the pupils in the intervention and 16% in the control group were not included in the final analysis. Therefore there were some potentially important differences in characteristics between the intervention and control groups. This undermines the security of the result. The reason that so many pupils from schools implementing PBL are missing from the analysis is largely due to five of these schools leaving the trial before it finished. The amount of data lost from the project (schools dropping out and lost to follow-up) particularly from the intervention schools, as well as the adoption of PBL or similar approaches by a number of control group schools, further limits the strength of any impact finding.”

So, almost half of the schools had to drop out (for reasons which we’ll come to in a moment). Furthermore, the intervention period was meant to be two years but, due to funding constraints, this was halved. This is significant because most PBL experts agree that it takes 3-5 years before teachers really feel confident delivering a different pedagogical approach, and can therefore expect high quality student outcomes, whereas one can assume that the control group of schools have been working in their ways for some considerable time.

And if that’s not enough to cause doubt, consider this from the report:

“ for some that did not get allocated to the intervention group, faithfully adopting the control condition was seen as being detrimental to their pupils’ learning and therefore some of these schools chose to implement a version of PBL anyway.”

(Full disclosure: I can confirm this took place. Although I’m a Senior Associate at the Innovation Unit, who managed the trial, I was not part of the team. I do, however train schools in the use of Project-Based Learning. I discovered at the end of a training event that the school I’d been training were part of the control group and were intending to introduce PBL to their students. Contamination of evidence is anathema to educational researchers and further undermines the usefulness of the conclusions.)

Another central tenet of randomised control trials is that like is compared with like: if you want to know whether an intervention will improve literacy scores, you should have schools that were comparable before the intervention began. According to the Innovation Unit blog post in response to the report: “8 of 11 schools in the study were ‘Requires Improvement’ (an OFSTED categorisation indicating cause for concern) or worse (national average is 1 in 5)…The control group were stable in comparison, with 8 of 12 schools Good or Outstanding” .

So, here’s the nub of it: the newspaper article claimed that the report demonstrated that “FSM pupils in project-based classes made three months’ less progress in literacy than their counterparts in traditional, subject-based lessons.”

But this was based upon literacy data from schools – 80% of which would have already had poorer test scores than most of the control group schools. Is it possible, therefore, that the kids tested might have actually been further than 3 months behind their control group counterparts, without the PBL intervention?

Let’s use a simpler analogy in order to highlight this flaw: If you feed me anabolic steroids for a year, I’ll still come in a long way behind Usain Bolt in a 100m race. Surely a more sensible test would have been to see if my own personal times improved after the ingestion of drugs, not whether I was able to beat someone already faster than me?

Some on Twitter justifiably asked why was almost half of the data missing from the intervention schools, but not the control group? It turns out there were a variety of reasons, most of which point to the difficulty of carrying out trials in the fear-driven English schools system. 5 of the 12 intervention schools withdrew during the trial. 3 had a change of headteacher (presumably in response to OFSTED judgements), 2 were taken over by academies. 1 withdrew after the trial was cut from 2 years to 12 months. One school refused to submit its students to the test, arguing (with some justification) that you can’t hope to see improvements in literacy scores 12 months after introducing PBL.. If you, as a leader, were facing future closure if results didn’t improve, would you introduce a significant change like project-based learning, or knuckle down, and overdose on test-prep? Yep, me too. So, does it make sense to study the impact on such schools?

Before I get on to the two ‘J’Accuse’ parts of this post, allow me to share a few quotes from the evaluators report:

“ it is not possible to conclude with any confidence that PBL had a positive or negative impact on literacy outcomes”

“ schools reported finding positive benefits from the programme in terms of attainment, confidence, learning skills, and engagement in class”

“ the Innovation Unit’s Learning through REAL Projects implementation processes were particularly effective for the target (that is, willing and with the capacity) schools, and the feedback from those schools was almost entirely positive.“

“The need for improving skills appropriate for further study and those valued by employers in the modern workplace (a central aim of PBL) has not diminished, but probably increased. This study picked up the value of these skills to pupils’ learning and future potential through the process evaluation, but was not able to measure these skills as an outcome.”

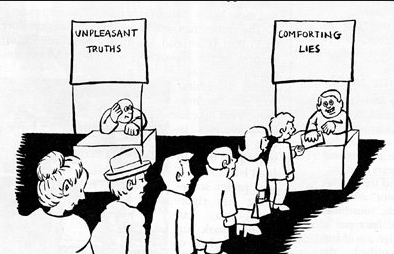

Were any of these quoted by the TES? Of course not. I realise that “Study Doesn’t Prove Much Of Anything” is a kind of headline more suited to The Onion than the TES, but journalists have a responsibility to provide balance, especially in the education press, as we’re living in an evidence-based era. If they don’t provide that balance, we may as well just forget about truth and see who can shout the biggest lie. The evaluators, it seems to me, did a good job in presenting a fair and balanced assessment, working within the constraints of a difficult set of circumstances, on a project that probably should have been curtailed when so many schools dropped out.

It’s just a pity that the ideological bias of our media sought to significantly misinterpret it.

Which brings me to my second accusation. I don’t think I’m being unfair when I say that, in the increasingly fractious educational debate between ‘traditionalists’ and ‘progressives’, there are a greater proportion of traditionalists who say that we should objectively look at the evidence, and make informed policy and practice decisions, on the facts, not misinterpretations.

So, it was particularly disappointing to see some of those same people jump on the TES headline, rather than reading the evaluators report. Sadly, this includes Nick Gibb, Minister of State for School Standards:

and Sam Freedman, Director of Teach First:

and SchoolsImprovementNet:

And a host of others on Twitter.

Rachel Wolf, of Parents and Teachers for Excellence, was quoted in the TES article (because I’m sure she’d read the full report), citing students doing a project on slavery, baking biscuits, as evidence that PBL taught the wrong things. I shall henceforth remember her fondly as ‘rigorous Rachel’. In their defence, the TES at least shared quotes from some of the intervention schools. One of these schools that’s presumably been failing their Yr 7 students was Stanley Park High School. In an unfortunate disjuncture, this same school had just been awarded 2016 Secondary School of the Year by…the TES. You couldn’t make it up. Oh, wait, they just did.

In my attempts to get some of the above to read the original evaluators report, in full, before exercising their prejudices, I was accused of dismissing the evidence. I’m not. I’m the first to say that the evidence based for PBL is weak (though stronger than many claim, and the evaluators have done a good job in presenting the key messages from a literature review). Many people who see very positive impacts of PBL (in extraordinary schools like Expeditionary Learning, High Tech High and New Tech Network in the USA) are very anxious to see large-scale, reliable research emerge on the breadth of impact of PBL.

But, until we have that, can we stop hysterically distorting what little evidence we have? The rising popularity of PBL around the world has enthused and revitalised legions of classroom teachers. Until we’ve got some conclusive evidence that it’s not working, can we allow them to exercise their own professional judgement, please?

]]>Most new educational theories are developed using the experimental science model, where an external academic – or sets of academics – set up pilots using small groups of schools. These pilot programmes are often sold as ‘evidence-based’ randomised control trials, where variations are minimised (RCTs hate variations) in order to replicate laboratory conditions. Now that RCTs are all the rage in education, schools are increasingly not fashioning their own innovations.

Instead, they’re told what they need to do by regulatory authorities based on experimental science research initiatives. The exhortation goes like this: “we’ve worked out ‘what works’ – now you need to do it”. The problem is ‘what works’ doesn’t – or rather it works, but only if your school happens to share most of the same contexts and conditions that were seen in the original pilot. And that’s the point: schools exist within messy, complex and various contexts. ‘What works’ silver bullets frequently turn out to be duds when scale-up happens. And it is often in scale-up stage, when less than impressive results occur, that two opposing educators can cite completely contradictory evidence. Or two opposing politicians citing the evidence that suits their world view, hence the phenomenon of ‘policy-based evidence making’ (and not what they claim to be ‘evidence-based policy-making).

So, if the experimental science method is flawed, is there any alternative? Thankfully, yes. And the good news is that it puts schools back in the driving seat when it comes to ‘getting better at getting better’.

We’ve recently begun training school leaders and teachers in a new, exciting, approach to building a culture of adult learning and a culture of continuous improvement. Our excitement stems from the possibility – and it’s so new that it’s only that – of this approach unlocking the key to the holy grail of educational reform: self-improving schools (and teachers). It’s called Improvement Science.

What is Improvement Science?

Improvement Science has been around for a long time – pioneered by the management genius, W.E. Deming. It has been used successfully in the aviation, automotive and healthcare industries and now the Improvement movement has finally reached education. It provides a different slant on innovation, offering an alternative to disruptive change, by supporting educators in ‘getting better at getting better’. It’s not a one-off event, or pilot initiative, but rather a continuous cycle of incremental gains. Despite the simplicity of the approach, spectacular results have been achieved, using improvement methodology:

- In sport, Sky cycling’s boss Dave Brailsford championed the “aggregation of marginal gains”. Believing that if they only made

Team Sky: “The aggregation of marginal gains”

1% improvement in any given aspect of planning, but made enough gains across the board, they could win the Tour de France within five years. He was wrong – they won it in three years;

- In some US hospitals mortality rates from severe sepsis have halved in less than three years, through a focus upon improvement methodologies;

- Through adopting W.E. Deming’s improvement cycles, Japanese companies like Toyota and Sony came to rapidly dominate their markets.

Fine, but what’s this got to do with learning and engagement?

The recent history of educational reform has seen a slew of data-driven targets, imposed ‘solutions’, increased accountability (also known as ‘fix it, or else’) and the growth of mandates and inspections. Despite decades of increased effort and expenditure, the returns have been disappointing, and good practices obstinately refuse to scale. Deming argues that imposing targets only breeds fear and corruption, and that sustainable change can only happen when the practitioners themselves (in this case teachers) become the change agents; when end users (in this case students) are central to the processes being tested, and when improvement is seen as a continual process.

At its heart, the Improvement Science model only seeks to answer three questions:

1. What are we trying to accomplish?

2. How will we know that a change is an improvement?

3. What changes can we make that will result in improvement?

Behind these deceptively simple questions, however, lie a complex set of variations (for example, why does a change work in one context but not another?) and, as we’ve seen, variation is the norm for most schools. These questions also infer a profound shift – from privatised practice, to a culture of open learning. If Improvement Science can achieve dramatic impact in the complex and specialised world of healthcare, why can’t it work in the equally complex world of learning?

For schools, taking an Improvement Science approach and joining – or creating their own – Networked Improvement Communities is reclaiming some of the ground that’s been conceded to others who have determined the agenda they should follow, the song they should sing. It will almost certainly lead to performance gains but, because of the Hawthorne Effect (where any innovation usually creates short term benefits) that isn’t the point. Schools who commit to cycles of continuous improvement are more likely to see sustained long-term, performance gains. More than that, however, is the prospect of schools becoming collaborative centres of open learning, sharing what they’re learning in an open culture, where access to internal knowledge is free and practitioners are trusted to find their own solutions. It’s this culture shift, that we’re seeing in the early schools we’re working with, that is so exciting.

So, how will this work?

We’re looking to partner with a small number of schools, clusters of schools, and administrations in creating open learning cultures through learning how to improve. We continue to believe that engaging learners is key to their long-term chances in life. But engagement alone, isn’t enough. Because if we want deep and engaging learning for our students, and if we want successful practices to scale, then we also have to have in place what Tony Bryk, of the Carnegie Foundation, highlights as the other two ‘e’s: effectiveness and efficiency. Improvement Science offers a route to self-determination in all three of those elements. I’d urge educators to consider adopting Improvement Science methods in their schools – if nothing else, it’ll put an end to those silly Twitter spats.

]]>If you’d like to vote for us please CLICK HERE.

Please note that votes are accepted from anywhere in the world – we know we have a lot of international readers – all are eligible to vote! But hurry, voting ends April 9th midnight (UK time)

]]>