The past few days have seen the opposite (if not equal) reaction to the recent emergence of the #EducationForward campaign. With scant regard for factual accuracy, various bloggers and tweeters (since they crave attention I’ll anonymise them for now) have attempted to summarise the Education Forward book, without the tiresome task of actually reading it. One, describing #EducationForward as ‘Education Backward’ (witty), linked EF to Class Action, the recently created magazine ‘by teachers for teachers’ (wrong). Others questioned how EF is funded (it isn’t). But the biggest (though I suspect knowing) misconception has been to cast Education Forward as promulgating ‘the vision of progressive education”.

The past few days have seen the opposite (if not equal) reaction to the recent emergence of the #EducationForward campaign. With scant regard for factual accuracy, various bloggers and tweeters (since they crave attention I’ll anonymise them for now) have attempted to summarise the Education Forward book, without the tiresome task of actually reading it. One, describing #EducationForward as ‘Education Backward’ (witty), linked EF to Class Action, the recently created magazine ‘by teachers for teachers’ (wrong). Others questioned how EF is funded (it isn’t). But the biggest (though I suspect knowing) misconception has been to cast Education Forward as promulgating ‘the vision of progressive education”.

If these bloggers had actually bothered to read the book, or watched Sir Ken Robinson’s opening to the recent conference, they would have seen repeated criticisms of the polarisation of education into Traditionalists and Progressives. So, only someone trying to pick a fight would deliberately cast the movement as one of the poles it is consciously avoiding. Education Forward’s objective is simply to change the conversation away from the same tired polarities (direct instruction vs discovery learning, academies vs comprehensives, etc) toward a much-needed discussion as to what kind of education system will be needed to enable young people to thrive in the future.

The people who attended the conference were talking about the need to adopt any teaching strategies that will help kids become more literate and numerate, globally aware, compassionate and curious, and equipped with the non-cognitive ‘soft’ skills that this week’s Education Policy Institute report argued are being neglected in the UK. One of the headteachers who spoke at the event was Mark Moorhouse, Headteacher at Matthew Moss High School in Rochdale. Mark talked about the school’s D6 initiative – recently praised by the government in its 2017 Parliamentary Review. I first observed D6, shortly after its introduction in 2014, and blogged about it here. I’ve just come back from a further visit, and it’s great to see that this non-ideological experiment now has clear evidence of its effectiveness.

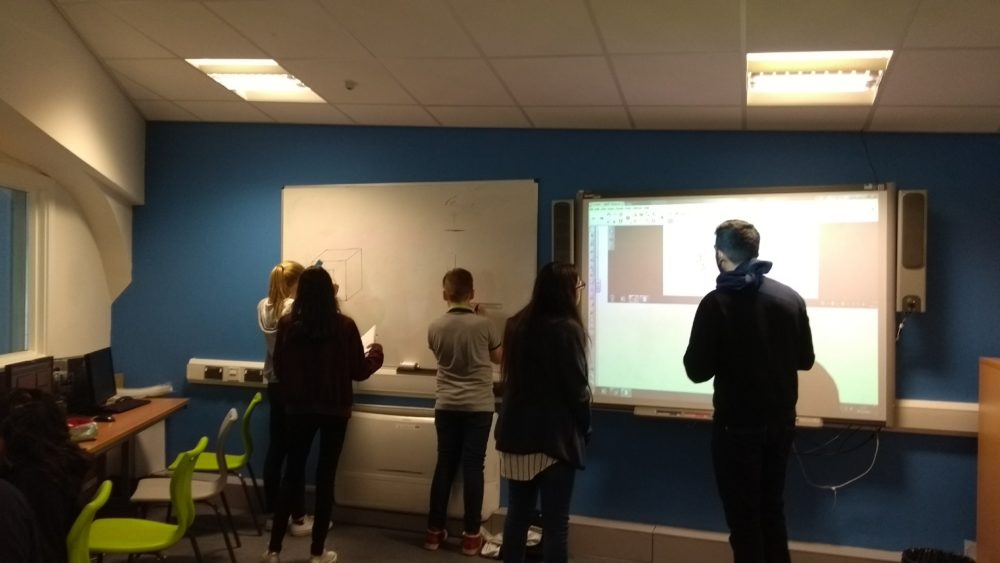

D6 operates on a Saturday morning and is a voluntary peer-to-peer learning experiment. Teachers are in attendance, but not in classrooms – they make tea for students and catch up on their marking. There are learning ‘coaches’ – students from the local sixth-form college, who are there to support learners – though some students prefer to work on their own. The content being studied is entirely determined by each group of around 3-6 students, so it’s impossible for the coaches to prepare lectures or worksheets in advance. Today was a relatively quiet day – just over 100 students turned up, largely because a new group of coaches are being recruited. Despite that, two floors of the school were filled with students, deeply engaged, and in charge of, their learning. With so much freedom one might expect to see students kicking a football around or playing video games. Almost all of the students I saw today were grappling with maths, chemistry or science problems. The school serves a large Asian community, and Rochdale is an area of high deprivation. I saw one group of white working-class boys (the so-called ‘hard to reach’) jubilant that they’d finally cracked percentages and overheard another say “I think I’m getting the hang of maths now” – the level of student agency was palpable.

But, here’s the thing: the actual pedagogy being deployed was often classic note-taking, demonstration and explanation stuff. On Monday, many of the Year 7s will be doing projects, some of the Year 8s will be getting a history lecture, while some of the Year 11s may be doing test prep – and there is no conflict. Only in the confrontational minds of some binary edu-tweeters is the question ‘which side are you on?’ even worth considering: for these kids, it’s all just learning. But Matthew Moss High School is future-facing, in so far as it passionately believes that a love of learning will be vital to their students’ prospects, because the future demands that we will all have to learn, unlearn, and re-learn throughout our lives. So, student agency over their learning is paramount.

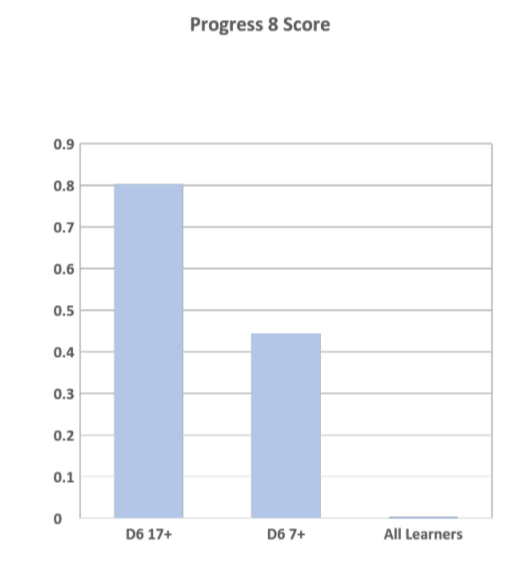

There are plenty of teachers that dismiss experiments like D6, arguing that research (they always seem to wheel out a single cognitive load study) ‘proves’ that novice learners need fully guided instruction and that ‘students are not good at making choices that optimise their learning’. Well, the students at D6 would beg to differ. Here’s the comparative test scores from last year’s D6 cohort who had attended 7 sessions, or more than 17 sessions, last year (overseas readers, please don’t ask me to explain how progress 8 scores work in England!):

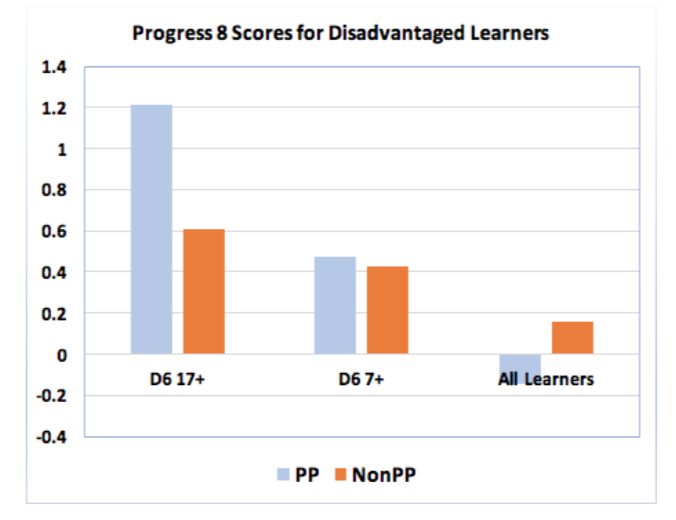

There is also a minority belief that anything other than direct explicit instruction, delivered by an expert to novice, will disproportionately penalise students from low-income backgrounds. Matthew Moss have analysed the impact of D6 upon students attracting additional ‘pupil premium’ funding (those in receipt of free lunches). Here, the figures are particularly striking:

So, the introduction of peer-to-peer learning is having a remarkable impact upon test scores, learner confidence, and learner agency – especially among students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Education Forward wants parents, business leaders and educators to know that there are other models of instruction – neither ‘traditional’ nor ‘progressive’ but a combination of the two (if indeed one can categorise pedagogies as lazily as that) – that don’t present either/or scenarios. They can deliver good test scores and equip learners with the self-sustaining dispositions they’ll need throughout their lives. (It seems to be only in the UK that we have this obsession with these sterile arguments – the rest of the world’s educators must think we’re still in the 20th century.)

I’d urge educators to visit Matthew Moss High School to see D6 in action.

I’d urge everyone not to be drawn into pointless polarising debates on pedagogy, but instead to ask ‘how do we need to change our approach to education, in light of the enormous, disruptive changes that we’re facing?’

And I’d urge you to look at Education Forward’s 10 goals of future-focused education and, if you agree, show your support.

Related Posts

Also published on Medium.

Social tagging: education forward > Matthew Moss High School > Progress 8