Ron Canuel, CEO of the CEA (Canadian Education Association) recently asked ‘why do we need innovation in education?’ I’m on the board of the CEA,’s professional magazine, so I have to declare an interest in blogging about this. But it’s a perfectly valid, if surprising, question to ask. Surprising, because it’s hard to imagine captains of industry asking themselves ‘do we need more innovaion in (say) manufacturing? Or medicine, or technology? But it’s valid to ask, because so few education innovations seem to stick, and scale-up. The ‘game changers’ rarely seem to change the game.

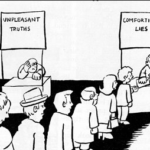

Ron, himself, gives one good reason for the comparative lack of innovation: that accountability frameworks don’t recognise innovation as a yardstick to be measured. So, education systems tend to value compliance , conformity, even complacency, above experimentation.

He’s right, of course, though just because we’re not being rewarded for innovation, is insufficient reason not to do it. Educators have a moral purpose – to strive to find the best learning for each individual in their care – and that should always trump keeping governments off our backs. That takes courage, of course, and school leaders, especially the less experienced ones, need time to build their courage. A Head Teacher of a highly innovative school in England, was taking a bunch of visitors around the school this week. He was asked ‘what progress have you made this year against the targets from the last OFSTED (our national inspections agency) visit?’ ‘None’, came the reply to a confused silence. ‘We haven’t tried to – it’s not important’. If only we had more school leaders who showed such determination not to be blown off-course by the constantly shifting winds of government. School leaders have a lot more autonomy than they often claim to have. But because it’s such a tough job, it’s sometimes frankly easier to work to the targets and priorities someone else has set for you, and blame them when it doesn’t work.

There are, however, another couple of explanations for the lack of innovation.

First, there’s the dreaded ‘guinea-pig’ syndrome, where any attempt to try something new is met with ‘so you’re going to use these children as guinea-pigs in your experiment, are you?’ I’m baffled by this reaction (and parents and politicians are equally guilty here) for two reasons: First, how many medical breakthroughs would we have missed if people had refused to take part in clinical trials? More accurately, it’s not the patients who are refusing the clinical trial. Kids generally enjoy being part of a new initiative. It’s the guardians of their interests who resist.

Second, there’s the ‘not-invented here-syndrome’ . Most of the truly exciting innovations in education are trialled on the ‘terminally ill’: the students for whom nothing seems to be working. But the treatment would work just as well on other students. The CEA have recently rewarded one such initiative: The Oasis Skateboard Factory. This is an alternative school in Toronto for kids for whom mainstream schooling just doesn’t work. I urge you to take a little time to watch it. Listen to Craig, the founder of the school, and listen to the students. And then tell me, what is it about this innovation that wouldn’t work in mainstream schooling?

It’s such a compelling argument for offering some kids (if not most) a more authentic, project and enterprise-based approach to learning. My experience of showing new models of learning to educators, or policy makers, usually gets the same reaction Ron Canuel refers to: ‘that’s interesting, but it wouldn’t work in our school’. When the Musical Futures model I helped develop was drawing attention from schools in other countries, I did the politically correct thing by saying that cultural contexts would need different approaches, and that student outcomes would probably be different. But, inside I was thinking, ‘kids are not that different all over the world, so this should work just the same, wherever you are’. The reality has been just that. In seven countries the impact on kids is pretty much the same, wherever you go, for the reasons stated so elequently in the Oasis video.

I’ve been researching business models of innovation for the book I’m writing, and it’s fascinating to observe the ‘innovation gap’ which blocks change. Sometimes it’s structural/cultural – disciplinary silos, circling the waggons with’professional standards’ (most innovations come from outside), specialists viewing attempts to change their established ways as implied criticism). Sometimes it’s managerial – CEOs of innovative companies (think Steve Jobs) spend twice as much time personally involved in innovation, than their counterparts in less innovative companies. You have to model the change you wish to see.

So, there are some long-standing reasons why innovation gets blocked, or fails to transfer. But these aren’t as insurmountable as we often proclaim, and we can’t let them get in the way. As to the orginal question being posed, here are my five top reasons why we need innovation in education:

1. Because student outcomes are flatlining in countries where the ‘do more, work harder’ dictat, combined with market-driven approaches from governments, drove innovation out of the sector and replaced it with fear. We need some new ideas.

2. Because, as educators, we’re in direct competition with the learning young people access socially, informally – and, right now, we’re coming off second best.

3. Because we need to constantly engage in respectful, challenging, professional discourse about our practice (and we need to spend rather less time providing pointless information to satisfy demands for accountability)

4. Because children, far from considering themselves ‘guinea pigs’ actually enjoy being part of something new. They well understand that being part of an innovation that doesn’t ultimately work isn’t going to have a critical effect on their education – not least because of (2) above. But the critical point is ‘being part of’, being active co-designers of learning innovations.

5. Because the one-size model of schooling never did fit all students, and it certainly won’t now. The school of the future needs to be an amalgamation of many different learning models, which students and teachers can try out to find what works best for them.

But what are yours? Please let me know your reasons for demanding more innovation in eudcation, and let CEA know here.

Very thought-provoking, intelligent blog, as ever, David! A key reason for needing innovation? Well one reason might be that the world’s population has doubled in a century and will double again in much less than that unless we do something. Learning facts, skills or just the core subjects at school is not enough. It is innovative thinking which will help us break free of the thinking which got us to this dangerous situation in the first place.So I am deeply concerned about the current politicisation of education here in the UK, which completely ignores the importance of innovation, in both the processes and the content of education. The nature of innovation itself is that we learn the most from when things don’t go as expected. And because pressure is on us for swift results, we fail to recognise that success in innovation is also rarely found on the first attempt. Sometimes we have to dig deeply to find positive results. Ask any inventor! So we need more generative rather than reactive thinking. The question is: how do we build a safe environment for designers and leaders of education, and the young people themselves, to test new ideas, monitor the results and use them to refine the next steps, so that true innovation can flourish?

The problem with OFSTED is that if you are a good educator/leader and improve your students’ (experiences of and success in learning, they don’t care. They want you to tick boxes, not change lives….

Should have added, when they come and inspect your school, if you aren’t ticking their boxes they can force you to resign and force your school to be privatised. Quite an incentive to sell out on your principles to avoid that fate being foisted on your students.(Luckily OFSTED doesn’t have jurisdiction in Scotland, where I now teach.)

My son was exceedingly happy for his guinea pig status while attending OSF. Finally his individuality was recognized and encouraged and instead of being punished for it he was rewarded. Along with this success came a high school diploma that seems to be the only way to move forward to both higher education and employment.

Tina, that’s such a great comment! I’m sure Craig will be delighted to read it, and I’m sure your son has gained so much more than a diploma, which be of benefit to him later in life.

Wonderful work and insights, David! Too bad the system doesn’t really accommodate Multiple Intelligences until these kids have failed for years…

I believe Craig said it best in the video when he discussed relevancy and value. There is very little of either in today’s system. We have a disconnect between learning for the sake of learning and what the powers that be think students should be learning.Relevancy = value, and students should value their education.