“It is not what you put into the child, but what you draw out that constitutes education.”

BH Montgomery Head, King Alfred School 1945-1962

This has been one of those weeks that I suspect I’ll remember for a very long time. A week ago, I was giving a keynote at King Alfred School, in London. The school is an independent school and, if I’m being completely honest, not one that I would have spoken at in the past.

I’m so glad I decided to accept the invitation to speak there.

The occasion was the Annual Conference of the King Alfred School Society, the group that has steered the philosophy of the school since its inception in 1898. It was born out of frustration with Victorian schooling, and, as the film below shows, placed a strong emphasis upon values that are pretty much unchanged, today: Mutual respect; Individuality and self-reliance; Social responsibility; Freedom, play and the enjoyment of education; A broad definition of success. That’s quite a list, and as current today as it was then.

Its Head Teacher, Robert Lobatto, made it clear in his introduction that the purpose of the day was for staff, parents and visitors, to be challenged as much as inspired. Robert speaks to what W.E.Deming would call a ‘constancy of purpose’, when he says, “Passing examinations is important. However, we want our students to take them in their stride, and value their learning beyond the exam grade. Students will also experience the moral dimension of learning.”

I decided to use the occasion to highlight the almost complete dominance of a narrow, results-obsessed (thanks mainly to PISA) story of what schooling should look like. Progressive schools, at least in the state sector, are under unprecedented pressure to sacrifice all the components of a well-rounded education, in pursuit of literacy, numeracy and science. The arts are being squeezed out of curricula, as are those who advocate any form of ‘independent learning’. The fixation upon ‘keeping our children safe’ means that it’s impossible to imagine the King Alfred ritual, where every child has to climb the school tree, happening in many UK state schools. The King Alfred Year 8 students also create ‘the village’, where they build huts, eschew electricity, phones and the internet, and work out their own community, living together for a week – such projects may happen in many UK schools, but I’ve yet to come across anything quite like ‘the village’.

We have to accept that in countries like the UK and the USA, schools are increasingly becoming regimented, joyless, exam-factories. The increases in mental health issues among our young people are truly alarming: a doubling of depression between the 1980s and 2000s, and a 75% increase in self-harm cases, over the past five years, in British young people; a 44% increase in adolescents accessing mental health services in the USA, between 1998 and 2012; steadily increasing rates of attempted and actual suicides on both sides of the Atlantic. Of course, there are many factors behind these increases, but increased anxiety to get good grades, in order to get into university, is real.

So, the gist of my talk was this: the current perception of a ‘good’ school being defined only by their test scores, has become so all-pervasive, that we now need to create a different narrative around the purpose, and outcomes, of an education worth having.

I thought of King Alfred this morning when I read this article from the Washington Post, on the injection of ‘joy’ as a character strength in so-called “no excuses” charter schools. Now, I get it with the ‘no excuses’ argument – if your mission is to close the achievement gap, then inner-city kids probably need to have their expectations raised. But if the only way to achieve good results is to make students quiet, submissive droids (if you want to see what submissive students look like see this video), and then have ‘joyous interludes’, then you’ve lost the argument. The article highlights one school, Achievement First, where the prescribed ‘joy’ in the classroom consists of making kids do the following chant: “Hey hey hey, I feel all right,” followed with a stomp. The phrase is repeated with two stomps, then three stomps and finished off with: “I feel motivated to learn. And graduate college.”

When I read this kind of stuff, I’m trying hard not to think of the last time I heard African-Americans being told what to chant, in order to make them more productive. Instead, I like to think that, however well meaning their aim, their short term results (there’s no doubt that test scores will improve when you push kids through a high-intensity sausage machine) are offset by the long-term absence of independent and critical thinking. The long-term prospects for these kids are not being helped by this kind of logic: yes, we know we tell you what to do every second of the day, and because that’s dispiriting, we’ll mandate episodes of joy by telling you what to chant. KIPP Triumph Academy’s handbook explains it this way: ‘For fifth-graders, learning to chant their multiplication tables during summer school is an essential part of their KIPPnotizing’.

Wouldn’t it be simpler just to stop the brainwashing, and commit to making learning joyful wherever possible?

I spent the rest of the week with leaders from some of the most innovative schools in the world, visiting schools in Denmark. Although the Danish government is nudging school improvement down the ‘test scores are all’ route, what we saw were academically successful schools that still believe in giving students a well-rounded curriculum, and the space – and time – to discover who they are, and the kind of future they want for themselves.

And here’s the thing: it’s not an either/or. Hellerup School and Ørestad Gymnasium, both in Copenhagen, share very similar characteristics to King Alfred School: they get good results, but they’re developing students’ abilities to problem-solve, think imaginatively, and show empathy and compassion for others. Their students don’t seem to be stressed, (Denmark has, after all, been rated the happiest country in the world) and they really enjoy coming to school.

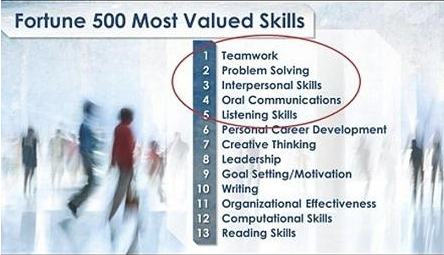

When the school leaders (from USA, Cambodia, Australia, India, Denmark and the UK) got together to make sense of the week, a clear message emerged: we have a growing evidence base that demonstrates that what governments are telling us we need is diametrically opposed to what the majority of parents, employers and students want from our schools. Take a look, for instance, at this list of Fortune 500 companies ‘most valued skills’ list:

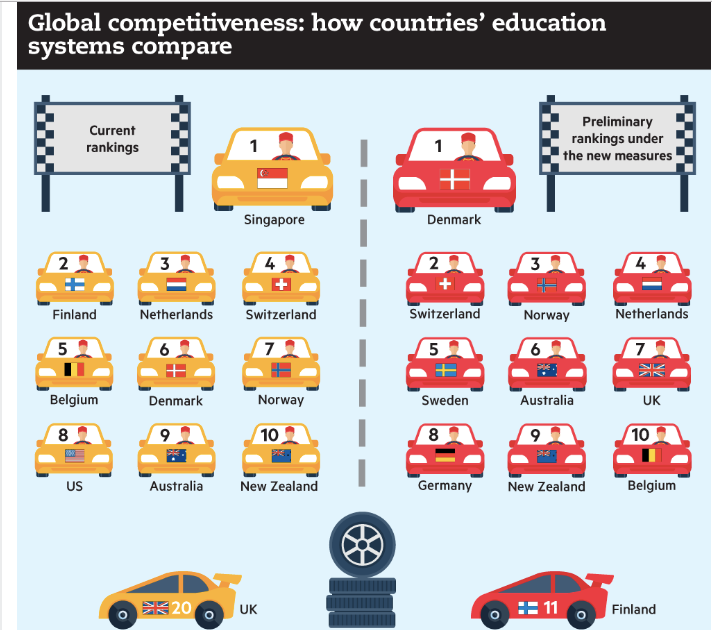

The PISA rankings offer a much too narrow assessment of students capabilities. Thankfully, the World Economic Forum has just announced that it will ditch its current criteria – including quality of maths and science, and how well schools are managed, in favour of student’s preparedness for the new world of work. This aligns with the Fortune 500 most valued skills, ranking students by a range of measures, including ICT skills, collaboration, critical thinking and problem-solving. This shift tells a very different story:

World Economic Forum: On the left – current assessment of core subjects and school management. On the right: preparedness for work

And it’s striking how none of the Far-Eastern countries that dominate the PISA rankings feature in this more rounded assessment of student skills!

If we’re really going to give our kids the best preparation for an increasingly uncertain world beyond school, (not to mention saving the sanity of a dangerously dispirited teaching workforce) then we have to forge alliances wherever we can find them:

- We can’t allow independent/government schools to ignore one another, so that we can accumulate the necessary evidence that you can have both well-rounded, happy, employment-ready citizens whilst still achieving good academic outcomes;

- We have to give voice to parents’ concerns that their kids’ welfare matters more than improving the national PISA ranking;

- We have to amplify the voice of business leaders when they tell us that the current ‘teaching to the test’ regime isn’t giving them the workforce they need;

- We have to find ways to measure the skills and aptitudes that might not show up on a standardised test, but matter just as much;

- We need to show the positive impacts of a more progressive and humanistic approach to schooling: a lifelong love of learning; a reduction in mental health issues; the ability to think for yourself; the opportunity to find your ‘element’ through a rich and broad curriculum; the development of skills that employers are crying out for.

I’ve written this post after talking with a number of very experienced educators. I think it’s fair to say that we all feel that a cross-sector coalition of parents, employers, teachers and students could create an idea whose time has come. Then again, I could be sitting in the middle of an echo chamber.

So, please leave a comment below (“even if it’s just an ‘agree/disagree’). Is it time to reverse the results-driven direction we’ve been heading in for decades, and, collectively tell a different story?

Related Posts

Also published on Medium.

Social tagging: Hellerup School > King Alfred School > KIPP > Orestad Gymnasium > PISA > World Economic Forum

David, enjoyed reading your blog post. If you are sitting in an echo chamber so am I (guess we shared it last week). And so are the educators we meet, work and discuss with in Denmark and across the world. We are at a point in history where school is no longer necessary to learn basic knowledge and skills, and where school as we know it can take on completely different forms. We are at a point in history where children and young people could in fact very much shape their own education through a rich and varied provision in strong learning communities and networks that will turn out young people who know who they are, what they care about, how they can contribute and how they learn in joyful, passionate ways. To quote a participant at one of OECDs recent Idea Factories, ‘humanities and liberal arts are as important as the natural sciences for developing a strong labour market. Why? The top jobs of 2025 will be 50% based on humanities and 50% based on natural science.’ We have yet to put that focus (back) into our schools. The emergence of technologies like social gaming, AI, VR and more makes it very clear that we need cross-curricular challenges to a much larger degree in our schools, with an increased focus on humanities and not least the arts, and on skills like empathy, the ability to listen, to engage, to collaborate, to innovate. Even with our well-rounded approach to education in Denmark we know that as many as 25% of our learners often feel bored in school. It testifies to a school system (of which Denmark is no more guilty than the rest of the world) where we have taught students to disregard their own interests and passions as well as their natural desire to engage and create. It is simply not asked for, at least not in ways that are sufficiently meaningful to our students. And so we continue to put on the show called school where students pretend to learn things that society pretends are really important while the world is changing before our very eyes.

A great summation of where we are right now: many thanks.

I think that an important point also is that a broader and more robust experience of school than practicing memorising content for the test would serve to strengthen real intellectual capital within a society. Longitudinal studies show this and schooling for both personal happiness and the economic well-being of the nation is a much longer and deeper game than that being played at present.

At the end of the day, we can have everything we need from an educational system, if, as in the face of any problem, we are collectively thoughtful, deliberate and creative.