My friends at Canada Education have just published a piece I wrote for them on why schools find it so hard to innovate. I’d really recommend that you read it in its original context (not least because you’d see lots of other excellent articles). But, if you would rather read it now, here it is:

In 1968, Spencer Silver, a scientist at one of the world’s most innovative corporations, 3M, invented an adhesive that left no  residue. Unfortunately, it didn’t really bind anything either and, as a failed experiment, it was quietly forgotten. There was – and still is – nothing remarkable about a failed experiment at 3M. Over half of their inventions never make it into production.

residue. Unfortunately, it didn’t really bind anything either and, as a failed experiment, it was quietly forgotten. There was – and still is – nothing remarkable about a failed experiment at 3M. Over half of their inventions never make it into production.

Eight years later, another 3M scientist, Art Fry, was getting frustrated in church. The makeshift scraps of paper he was using as bookmarks for his hymnal kept falling out. Remembering Spencer’s glue that didn’t stick, Art started tinkering with paper-backed adhesives to create a removable hymnal bookmark.

We know it today as the Post-It note.

It’s a classic example of the capacity, in the words of an equally successful company, to “fail fast and iterate.” Google got the idea for their famous 20 percent “free time” (where employees can spend a day a week doing their own projects) from 3M, who first instigated 15 percent employee time in 1948. Google has only a slightly better failure rate than 3M: 36 percent of Google’s inventions fail, though many of their failures have successful iterations further down the line.

To those of us working in education, the culture of innovation lived by Google and 3M seems both fearless and enviable. How many of us would keep our jobs if half of what we tried didn’t work? How many of us are given generous amounts of time to experiment in our practice?

Due to what we in England call the “accountability framework,” most school leaders would be more likely to describe themselves as fearful, rather than fearless. Innovation happens slowly, and incrementally, in public schooling. The fear factor hangs over education ministers, who have to show an impact over a four- to five-year electoral cycle. It hangs over school and district administrators, who have to demonstrate “turnaround” in failing schools. And it hangs over teachers and students, who seem to be continually exhorted to “do more, work harder,” not “reflect more, work smarter.” The fear factor is one reason why, as Sir Ken Robinson remarked, “we keep trying to build a better steam engine” rather than radically re-invent education. Most would acknowledge that, compared to the incredible rate of innovation over the past 150 years in science or industry, things move slowly in education – and it can’t be because we think it’s about as good as it gets.

In working with teachers and school leaders in the U.K., Australia and North America, I’ve witnessed periodic periods of fear and demoralization. I believe that while some of those fears are justified, some are not. Before looking at ways in which we can stimulate schools to become more innovative, let’s look at what seems to be holding us back, structurally and culturally.

Structural innovation blockers

“It’s the system.”

In the U.S. and England (where, arguably, the fear factor is greatest), current strategies seem to involve carrots and sticks. The Obama administration recently completed the first three-year cycle of the Investing in Innovation program, dedicated to finding “innovative solutions to common educational challenges.” The English equivalent is the Education Endowment Fund, instigated to encourage innovations to “break the link between family income and educational achievement.” While the change of direction from both administrations, previously “best known for mandating compliance and disbursing formula funds,”[1] is to be welcomed, both funds have been criticized for overly narrow eligibility criteria and overly prescriptive evaluation requirements.

The top-down fostering of innovation also has to be seen against what is perceived by school leaders as an ever-increasing emphasis upon standardized testing and payment by results.

“They won’t let us innovate.”

After lengthy demands for compliance, it’s perhaps understandable that school leaders would be hesitant about taking the path less trodden. When, in 2005, the Innovation Unit[2] was part of the U.K. Labour government’s Department for Education, it was mandated to offer schools the “Power to Innovate.” This gave schools temporary exemption from statutory regulation, should their innovation benefit from it. An overwhelming majority of schools who applied for this exemption were advised that they didn’t actually need it – what they were proposing lay within the regulatory framework anyway.

Once established, a culture of compliance is remarkably difficult to break.

“Innovation flows down, not up.”

Many teachers have experienced, over the past decade, some loss of autonomy in their practice. The introduction of the Common Core Standards in the U.S. is perhaps the latest example. Accompanying this has been the rise of the “executive leader” of schools. Once charged with turning around a failing school, such administrators inevitably bring sweeping change into the organization, reinforcing the notion that for teachers, innovation is done to them, rather than done by them.

In sharp contrast, the growth of personal learning networks, social media and social learning phenomena like TeachMeet events[3] are reversing this pattern. Teachers engaging in peer-to-peer learning offers the best hope not only for innovation flowing upwards, but also for models of distributed leadership.

I have experienced this first-hand through the Musical Futures program.[4] Musical Futures has been engaging students for 11 years, originating in England, but now operating in seven different countries, including Canada. We learned some time ago that the way to get an education innovation to spread was by engaging teachers in develop-ing new practices: prototyping, testing, reflecting, redesigning. But we started in a single country, before the advent of social media. Now, Musical Futures teachers globally share their videos, resources and lesson plans through a virtual sharing wall, Facebook, and a weekly Twitter meet-up. One tweet from a teacher sums up the excitement felt by this form of global, do-it-yourself professional development: “This is the best staffroom EVER!”

Cultural innovation blockers

“Why should my child be the guinea pig?”

I was once explaining an initiative I was leading to an English politician, only to be halted by the phrase every education innovator dreads: “So, you think it’s OK to treat these kids as guinea pigs, do you?” This populist favourite is inevitably followed by, “Kids only get one chance at a good education.”

Indeed they do. But, while I have met many children whose schooling was blighted by mind-numbing repetition and routine, a child’s school career is long, and I have yet to meet any who felt they were penalized by being part of a new innovation. Quite the reverse – most students are happy to be seen as pioneers of a new form of pedagogy. The demand for places at charter schools in the U.S., and free schools in the U.K., suggests that parents, too, are less concerned about the guinea-pig syndrome.

“If all else fails, or no one’s looking, innovate.”

Schools, in most developed countries with strong accountability frameworks, aren’t judged on their levels of innovation. They are judged, primarily, on test scores. There is, therefore, precious little incentive for good mainstream schools to try new teaching practices which ultimately may not work.

Radical, disruptive innovations are most frequently seen in so-called failing schools, where tweaking or incremental change is insufficient. Hartsholme Academy, in Lincoln, U.K., is a prime example. When Carl Jarvis became Head Teacher there in 2009, the school was under threat of closure. It was ranked the 5th worst school in England.

The fear factor, however, was absent, since there was no realistic future for the school. Carl changed everything – except the teachers he inherited. Out went desks, in came iPads for all students. Out went worksheets, in came immersive learning environments, project- and challenge-based learning, and pedagogy based upon latest neuroscience findings. Three years later, the English schools inspections agency deemed Hartsholme to be “beyond outstanding” (outstanding is the highest achievable classification). Despite this astonishing achievement, the Hartsholme innovations are dismissed by many as non-transferable, applicable only to failing, inner-city schools.

Charles Leadbeater has written extensively on our failure to learn from the innovations which take place “in the margins.” Because they are only in our peripheral vision, we fail to see their wider applicability. Leadbeater argues that solutions which are found in developing countries or in alternative educational settings are not just instructive, they are the future: “Too often, entrepreneurship and innovation have been seen as marginal add-ons. In the century to come, they have to become the new mainstream.”[5]

Feel the fear and do it anyway

One of the world’s leading management experts, W. E. Deming, believed there were five deadly diseases of management:

1. Lack of constancy of purpose – not understanding why we’re doing what we’re doing;

2. Emphasis upon short-term profits – leading to “shipping stuff out, no matter what,” and “creative accounting”;

3. Annual rating of performance – the merit system encourages short-term performance. It annihilates planning, it annihilates teamwork. You don’t get ahead by being collaborative, you get ahead by getting ahead;

4. Mobility of management – the valorising of those who can quickly turn around a company’s performance, but do so by a scorched-earth policy and then quickly move on;

5. Use of visible figures only – only valuing what can be easily measured.

It doesn’t take much imagination to see how these can be applied to many current national education policies, and how they contribute to a climate of fear and mistrust.

So how do school leaders navigate the murky waters between what social theorist Barry Schwartz describes as “doing the right thing, or doing the required thing?” Undoubtedly, the hierarchically imposed fear factor puts pressure on leaders to do the required thing. But there are enough inspiring examples of school leaders and superintendents who have felt the fear and done the right thing anyway to give us all hope. There is probably little we can do to persuade our political leaders of the need to do the one single thing which, above all else, would remove the fear factor: de-politicize education. But there is plenty we can do, as a community of practitioners, to support innovation without fear.

First, we can look outside our own discipline for inspiration. It is, after all, what leaders of innovative schools do. Books by management gurus Peter Senge, Ricardo Semler, Teresa Amabile and Clayton Christensen are just as likely to be on their bookshelves as classic education texts.

Second, we can see that innovative organizations, like Google and 3M, create a safe space for experimentation, giving people trust, time and permission to fail.

Third, great leaders see their schools as porous global learning commons. When Stephen Harris, principal of Northern Beaches Christian School in Sydney, set up the Sydney Centre for Innovation in Learning, it was to ensure that his teachers would go around the world, visit great schools, and feel supported to embed those practices in their classrooms.

Fourth, leaders like Harris understand that innovation is a mindset, a culture, not a one-off experiment. To support that mindset they de-privatize the act of teaching, seeing teaching as a team sport, not a solitary activity. Critically, innovative schools seem to share a common characteristic: their teachers are expected to be designers of learning, not simply deliverers.

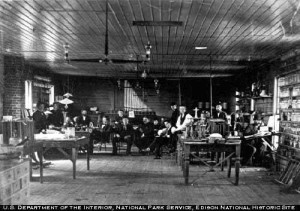

Fifth, centres of innovation have their own yardsticks by which they want to be assessed. Great schools aren’t blown off course by a single set of disappointing test scores. Instead they have a constancy of purpose, informed by their own success criteria, often less visible than those imposed upon them. Thomas Edison arguably created the most innovative learning environment wehave yet seen. Despite filing over 400 patents in six years, Edison insisted that his “inventions factory” at Menlo Park should be judged, not by its successes, but by the number of experiments carried out on any given day.

In most developed countries, we have a more conducive environment for innovation than we’ve had for many years – though not without restrictions. More importantly, perhaps, we are seeing global networks of innovators forming through social media. Instead of simply relying upon their schools or their leaders. they are being emboldened by each other’s ideas and mutual passion for learning. One of those taking part in the Musical Futures pilot was Sandie Heckel, a music teacher at the District School Board of Niagara, Ontario. This was her reflection on innovating within a community of practitioners:

“No longer was I the sole music/arts teacher in my school – I now had the support of teachers around the world who, like me, were going through the same struggles to get kids involved in authentic music making. This community of teacher learners, whose brains I could pick at any given moment through Facebook and Twitter, were an invaluable support. I especially appreciated seeing the videos of their students’ work posted on the Sharing Wall, as did my students.

In this project, the learning was collaborative, continuous, and evolved over time. It allowed me to struggle with new ideas and in the end make a fundamental shift in the way I teach – from almost exclusively instructing students how to make music, to facilitating my students’ collaborative search to make music of their choosing. The shift was radical and the shift is permanent, and the nature of this PD was key in making that happen.”

If experiences like Sandie’s aren’t enough to persuade us to overcome our fears, we have to consider the alternative. To simply continue teaching the way that we ourselves were taught – when the world is changing so quickly – is to be immobilized by fear.

As John Dewey said, “If we teach today’s students as we taught yesterday’s, we rob them of tomorrow.”

Hi David, this completely chimes with what we at FocusPsychology are advocating through our holistic and community orientated support of schools in the UK. Schools need to feel empowered to move away from labelling of children who don’t fit the very rigid system we describe as education in the UK and instead adapt the system to meet their school community needs. Learning engagement will inevitably follow, no quick fixes though!

Great article. We need to get into the heads of the policy makers don’t we? Yet they will be the most resistant. In Australia we have too many people in policy making positions in education that don’t know anything about their portfolio and make decisions that are about as informed as your average citizen on education. The other related problem is that most people are conservative by nature and education is a conservative culture. Like a bad curry it keeps on repeating itself.

I’m in Brussels in May giving some talks to the European Commission on Learning and Development and it is the policy makers that I most want to talk to. I think that’t the right approach.