This is the second post covering some of the themes behind my forthcoming book, ‘OPEN: How We’ll Work Live and Learn In The Future‘. The first is HERE.

This is the second post covering some of the themes behind my forthcoming book, ‘OPEN: How We’ll Work Live and Learn In The Future‘. The first is HERE.

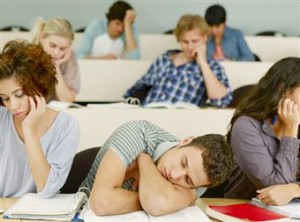

Someone asked me the other day why I’d written the book. It’s a good question. At least one of the motivations was to bring attention to one of the tragedies of the current socio-economic state we’re in: a global epidemic of disengagement.

A steady fall in engagement isn’t just affecting students – it’s become a feature of our working lives, and (witness the English riots, and the widespread apathy towards national elections) how we live socially. Levels of disengagement in both school and the workplace are pretty much identical.

Here are some stats:

The largest global poll of employee engagement found, in 2011, that only 11% of workers are engaged. 62% of workers describe themselves as ‘not engaged’, and almost a third are ‘actively disengaged’ at work

Recent estimates of engagement among English and Canadian students hover around 30%.

One consistent feature of educational disengagement globally is that the longer you are in the school system, the more disengaged you’ll become. 11th graders are twice as disengaged as 5th graders.

4 out of every 5 American students don’t see how school contributes to their learning, with 6 out of 10 not citing learning as the reason they go to school. Two-thirds of US students say they feel bored every day in school.

And the impact of this epidemic goes wide and deep:

Financial: The annual productivity cost of worker disengagement is estimated to be $300bn – in the US alone;

Worker turnover: Engaged employees are 87% less likely to leave their job; Customer relations: Engaged workers are 53% better at understanding customer needs;

Social mobility: A recent Australian study found that, ‘children’s interest and engagement in school influences their prospects of educational and occupational success 20 years later, over and above their academic attainment and socio-economic background’. In other words, an engaged student, from a disadvantaged background, is likely to have better life chances than a disengaged child from a better-off background.

Despite the appalling loss of human potential that comes with disengagement, both industry and education leaders seem myopic when it comes to addressing it.

In an age of austerity, CEOs could be forgiven for thinking that employee engagement comes a poor second behind financial survival. Making employees more productive might seem like a smarter move than keeping them engaged. A stream of studies in recent years, however, has demonstrated an irrefutable link between employee engagement, innovation and profitability. There’s a reason why those companies voted the best places to work in are also the world’s most innovative, and productive.

Prof. Julian Birkinshaw of the London Business School argues that ‘employee engagement is the sine qua non of innovation. In my experience …you cannot foster true innovation without engaged employees.’

Similarly, education policy makers have ignored engagement in chasing improved test scores, yet,as Alfie Kohn has said, ‘when interest appears, achievement usually follows’.

I believe there are two key reasons behind the falling levels of engagement in recent years: a loss of trust, and autonomy. The relentless push for profits and improved PISA rankings has eroded trust in workers and teachers alike: in a survey of trust in the workplace, a staggering 37% of employees claimed their boss had ‘thrown them under the bus’ to save themselves. The introduction of payment by test scores for teachers, has not only been proven – by Daniel Pink and others – to be ineffective, it also signals that teachers can’t be trusted to work hard because they love learning.

And we’re losing permission to think. The Guardian’s Aditya Chakrabortty paints a bleak scenario: “If you’re a bank manager you have far fewer individual powers than your predecessor would have had in the 80s. And if you’re a teller, it’s standard practice to work from a script… a high-up banker who used to be in charge of lending decisions (finds) his expertise has now been supplanted by a credit controller, described as “a software package that automatically assesses a loan application according to specific criteria”. In the near future, it’s estimated, only 10-15% of us will have “permission to think”.

The entitlement to be engaged by your work, or your studies, ought to be a basic human right. And the solution isn’t that difficult – focus on creating workspaces and classrooms as immersive, innovative spaces for learning, and workers and students will naturally become engaged.Not for nothing do Google employees refer to their comples in Mountain View as ‘the campus’.

Thomas Edison’s Menlo Park ‘Inventions Factory’ was probably the most productive and innovative company the world’s ever seen:. A group of just 24 workers managed to file over 400 patents in 6 years. A young graduate, Charles Upton, shortly after starting work there, wrote to his father: ‘I find my work very pleasant here and not much different from the time when I was a student. The strangest thing to me is that the $12 I get each Saturday for my labor does not seem like work, but like study and I enjoy it’. Thomas Edison grasped what so many of us have forgotten. Make work more like learning, and make engagement your number one priority, and results will take care of themselves.

OPEN: The Way We’ll Work, Live and Learning In The Future is published in October 2013, by Crux Publishing

In my opinion, it all starts when we’re kids and shortly after, teenagers. Now I’m no expert or wise elder, but as everyone else probably I have taken the same bate.

As soon as we reach 6-7 years old, we are being sold the “cool pill”; so instead of reading a book, we are told it’s cool to watch TV or play a video game, instead of using our head in school and get involved in constructive discussions, we are told to use our looks and be passive. Slowly but very surely we become locked in a world of our own, where it is cool “to do nothing” and and throw stones at someone who does try to. Corporations are the primary culprit, followed secondly by a disengaged government chasing votes and not change, real change, the kind that looks to bettering humanity “change”. The interests of these two groups seem to work very well together and have shaped the world we live in for the last hundred years or so.

And what a world we have today!

I don’t have a solution for the situation…yet, but personally as long as so much of the work force needs to think first about turning a profit and not about changing society for the better, we’ll always be caught in this Catch 22

The meaning and value of money in our society influences everything, top-down.