KQED’s excellent Mindshift blog recently featured an extract from my new book, OPEN. Many who visit this blog have already read the book, but I’ve included the extract, for completeness, below. What’s been interesting, however, has been the reaction to it. Appearing on Christmas Eve, I wasn’t expecting much of a response but there have been discussions on a number of LinkedIn forums and, generally, the reactions have been almost worryingly consistent. I’ll explain what I mean by ‘worrying’ below, but first, an extract from the extract (please visit the Mindshift blog for the full piece):

“Educational institutions have to grasp that having enjoyed an historic monopoly as the go-to-guys for learning doesn’t mean they always will. As we gained control of our listening with the arrival of the mp3, so we will increasingly gain control of our learning, thanks to the arrival of MOOCS, social media and informal learning. We will want to determine whom we learn from, and with whom, at a time of our pleasing.

Although this upheaval is currently taking place in tertiary education, schools are far from safe. As we find ourselves increasingly able to ‘hack’ our own education, I would expect, for instance, the homeschool market to expand rapidly. Once the possibility exists for students to study informally, at online (and offline) schools, compiling their own learning playlist, putting together units of study that appeal to their passions, the one-size-fits-all model of high school will appear alarmingly anachronistic. So, if educators want to keep their students engaged and inside their buildings, they have to look at the way they learn outside, and bring those characteristics inside.

Schools In Search Of A Purpose

If schools are coming into direct competition with the learning opportunities available in the informal social space, it has to be said that this is a pressure, which barely registers within the political discourse. Indeed, the gaping hole in the middle of the public debate on schooling is that we can’t even agree on what schools are actually for. Do they provide a set of skilled employees for the labor market? Or are they about developing the ‘whole’ child – emotionally, intellectually, creatively? Do they serve to ensure national economic competitiveness? Or are they about civic cohesion through cultural education? These are questions around which there has been no public consensus, as absurd as this may seem, given that in the U.S. and most of Europe we have had state-organized systems of compulsory schooling for over 140 years.

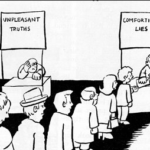

This failure to define a clear purpose has fatally held back progress in understanding how we learn best. For if you can’t agree on a destination, how can you possibly agree on the best route? Instead, what we’re left with is a public discourse permanently afflicted by the curse of binary, oppositional arguments. The either/or positioning isn’t helped by constant political interference, resulting in a series of pendulum swings with every change of administration. Polarized arguments prevent real progress being made: selective vs. comprehensive school systems; instruction-led teaching vs inquiry-led; head vs hand; academic vs vocational; knowledge vs skills. Can you imagine doctors in the 21st century arguing over the use of flu vaccines?

With No Particular Place To Go

It goes without saying that, if we don’t know our destination, and therefore can’t agree on the best route to get there, we might struggle to measure distance traveled. When I look at the radically differing educational strategies currently being adopted by most developed countries, I think back to how I learned to drive a car. Please allow this diversion. It has a point.

It was the late 1970s, in the Republic of Ireland, at a time when, inexplicably, learner drivers were allowed to drive unaccompanied. Working in County Clare, in the south-west of the country, my employer let me drive his car so I could prepare for my driving test on my return to England. One day, I was driving down winding country roads, and realized I was hopelessly lost – anyone who has experienced Irish road signs will know this is easily done.

Stopping a passing farmer, I asked if I was on the road to Kilrush, my destination. The farmer paused for some considerable time, looked up the road, then down at me, and pronounced “You are, but your car’s pointing the wrong way…”

So it is with educational policy. When the political pendulum swings in western nations, getting ‘back to basics’ in education (shorthand for focusing upon literacy and numeracy) becomes an easy exhortation. If confirmation is needed that ‘progressive’ methods have failed, one only has to cite steadily declining performances in international comparison tables like the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). This decline is then contrasted with nations like Singapore and South Korea, who excel in these assessments.

What is being measured is entirely dependent upon the intended destination. While the UK and US urge their schools to be more like those of Pacific Asian countries, the pressure there is to travel in the opposite direction. Addressing teachers in 2012, Heng Swee Keat, Singapore’s Minister for Education, argued for a radical shift in policy:

“The educational paradigm of our parents’ generation, which emphasized the transmission of knowledge, is quickly being overtaken by a very different paradigm. This new concept of educational success focuses on the nurturing of key skills and competencies such as the ability to seek, to curate and to synthesize information; to create and innovate; to work in diverse cross-cultural teams; as well as to appreciate global issues within the local context.”

These comments came shortly after South Korea’s ex-minister for education Byong Man Ahn cast doubt on the usefulness of a high PISA ranking, despite Korean students ranking first in reading and maths, and third in science, in the 2009 PISA survey:

“While Korea’s students excel at learning, they believe its purpose lies not in self-development based on personal interest or motivation, but in entrance into a highly ranked university. Students have no time to ponder the fundamental question of “What do I need to learn, and why?” They simply need to prepare for the test by learning the most-effective methods for digesting tremendous quantities of material and committing more to memory than others do.”

Both Heng Swee Keat and Byong Man Ahn were, effectively, repeating the advice given to me by that Irish farmer. Their respective countries had traveled a long way, but they’d realized that their car was pointing the wrong way. We in the West want to be more like those in the East, who, in turn, want to be more like we in the West. We call for learning fit to meet the challenges of the 21st century, while recommending teaching methods belonging to the 19th century. We have no clearly agreed purpose for education, but agree that spurious international comparisons should inform future educational policy.

In short, we’re really, really confused.”

The many comments I’ve received have offered a number of purposes for learning: independent leaners; global citizens; technologically literate; agile, adaptive, collaborative learners. No-one, not a single poster, argued for dominance of PISA Assessment league tables or ability to remember facts or mastery of ‘the basics’.

So, maybe ‘we’ (educators) aren’t confused about the purpose of education – though we could probably articulate it a little better. The looming crisis is the ever-widening gap between educators and policy makers (‘they’). We argue for a more holistic, longer-term purpose – they work to electoral cycles and short-term measurements. Why, for example, doesn’t Arne Duncan, the US Education Secretary, have the courage to say “For 50 years the US has been the innovation engine of the world, and during that time we’ve performed dismally in international education comparisons. PISA, shmisa….”.

We argue that we’re measuring the wrong things, and call for a wider set of measure – they mandate more standardisation and more prescription, with harsher consequences for those who fail to hit targets.

The real tragedy here is teacher morale. Education secretaries in many western countries are becoming openly dismissive of teachers protestations, labelling them ‘enemies of promise’ (or worse). You can’t transform any education system if you alienate the people who drive it.

The real tragedy here is teacher morale. Education secretaries in many western countries are becoming openly dismissive of teachers protestations, labelling them ‘enemies of promise’ (or worse). You can’t transform any education system if you alienate the people who drive it.

My impression is that teachers have no problem with being made accountable. But you can’t force self-improvement if you haven’t got agreement over your values. That’s Business Leadership 101.

So, how do start to get policy-makers and school and college leaders and teachers back on the same page? How can we re-align our values and purpose, so that morale improves and energies are directed into what really matters?

Please make your views heard. Because I fear 2014 could be the year when divisive cracks become chasms if we don’t start to get some sane, mutually respectful, public discourse going.

The change from being given an education or receiving an education to creating and crafting what you need when you need it will involve developing what I call “Learning Intelligence” (LQ). Summed up as the ability to manage your learning environment to meet your learning needs. Having analysed the 32 years of my teaching career to find out what works and why I realised it was LQ. I have written about this in depth covering the attributes, skills and behaviours involved in using and developing LQ. My long term aim is to bring this concept to the notice of teachers and learners in order to facilitate the changes we are seeing. You can find the first of 20 articles here: http://wp.me/p2LphS-3p Comments and feedback always welcome (it is part of LQ anyway!)

Kev